It goes without saying that the Covid-19 Pandemic has caused – and is still causing – disruptions to people’s ability to spend and companies’ ability to produce goods and to supply services. Moreover, the Pandemic looks set to disrupt the global economy for at least another six months and most likely somewhat longer.

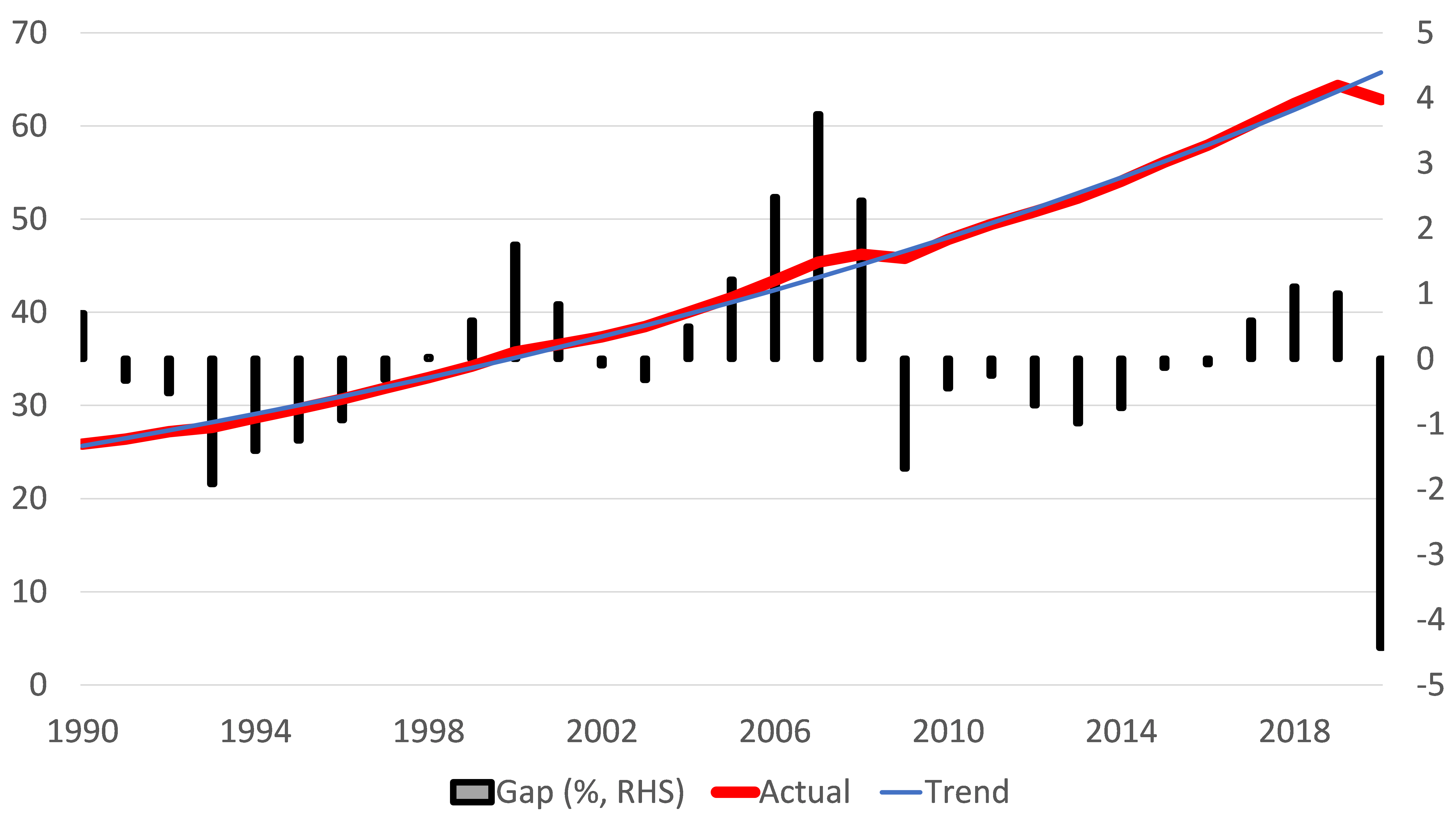

It is often forgotten, by many it seems, that the actual level of Real GDP that has been produced by the Global Economy will have been determined by the lower of either aggregate real demand, or aggregate real supply. Both aggregate demand and aggregate supply have fallen during the crisis but the problem for analysts is deciphering which side of the “supply and demand scissors” represented / represents the constraining factor on realized output. We can of course see by how much GDP declined numerically and by how much it is has declined relative to its prior trend, but the chart below tells us nothing about why the numbers are what they are – it is purely descriptive.

Global GDP and Trend

2017 Prices in international dollars

If we use the World Bank’s estimate of real GDP at 2017 prices and Purchasing Power Parity exchange rates, then we can suggest that “Global” GDP was around 4-4.5% lower than it might have been had 2020 been a more “normal year”. Of course, the estimation of PPP, let alone the trend rates of growth is highly suspect, but we would suggest that a 4% loss of GDP is probably not too far wide of the mark and this data also serves to emphasise that in a real sense, the world was indeed made poorer by the crisis, even if nominal stock market prices are now much higher….

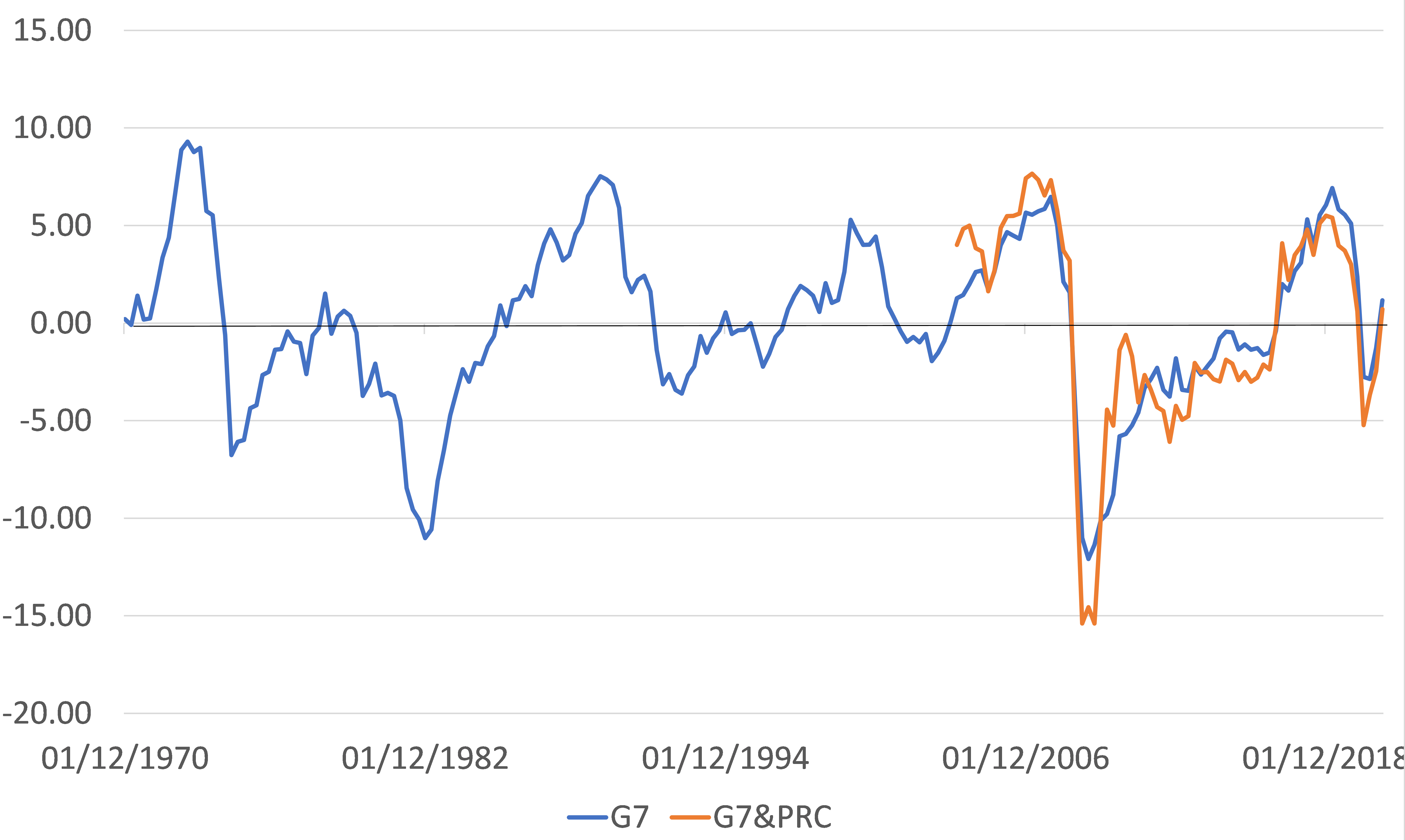

In order to discover which factor – supply or demand – has been the constraining influence on actual GDP, we have over recent weeks been developing our Demand Pressure Indices. We developed these indices back in the 1980s simply to answer the question of whether the rapid growth in the US, Japan, UK and Australia in the late 1980s was the result of structural or cyclical factors and the results proved both illuminating and useful. Today, we find that aggregate demand began to exceed aggregate supply during the closing weeks of 2020 and that by March this year the “World” was indeed working with a positive output gap. Furthermore, if we calculate a partial / flash estimate for 2021Q2, we find that it would be already back to its 2018 levels. The implication of this is of course that aggregate demand is higher than aggregate supply, or in other words that the constraint on real GDP thus far has been the Supply Side of the Equation. We regard this as being hugely significant.

Global Demand Pressure Indicator

For us, one of the standout features of the DPI chart above is that the Oil Shock of 1973 and the COVID-19 Shock of 2020 did not produce huge negative output gaps. The Volcker recession of the early 1980s and the GFC certainly did create substantial spare capacity and were therefore profoundly disinflationary or even deflationary, but the COVID-19 shock seems only to have created a small negative output gap and even this was relatively short-lived. Clearly, 2020 was very different to 2008, even though the authorities seem to have reacted in the same way…..

As many of us already know from our everyday lives, it is simply not possible to acquire many of the things that we might want to buy, be it certain cars, construction materials, a meal at our favourite restaurant, or even a new mast for the boat.

Supply disruptions, component shortages, logistical problems have all taken their toll on the supply side of the economy and, while these issues could initially at least be offset in some sectors via the simple expedient of running down inventories, even this option is no longer viable as inventory levels have plummeted over recent months.

It is of course not really surprising that it has been the supply side that has represented the binding constraint on real activity: policymakers can always create nominal demand (even if they have to spend the money themselves through fiscal policy), but actually making or supplying something involves real people wanting to, and being able to, work. That, of course, is harder to achieve during a pandemic.

Despite this almost common sense analysis, most policymakers and financial market analysts are not only conditioned to look towards a “Demand Stimulus” whenever growth disappoints (conceptually, we really have not moved on much from the Keynesian Demand management Policies of the 1960s and 1970s…), but also to look for inflation in the labour markets as a starting point. However, when supply is constrained by a lack of physical capacity, stocks, and components, it is highly unlikely that companies will be seeking to expand their work force or allow more overtime working – when there are physical constraints to output the labour markets are likely to be amongst the last places to experience inflationary pressures. Indeed, real wages are more likely to be falling than rising in such a world; the availability of labour is not the binding constraint on supply it seems. We suspect that these are the reasons that so many have been hoodwinked and surprised by the recent surge in global inflation rates.

Returning to our central theme, we know that in circumstances in which aggregate demand exceeds aggregate supply, markets can only clear if either there is physical rationing of demand (as in war time), or if prices rise to choke off demand so that it equates to the available supply.

Of course, economies are dynamic systems. As prices rise and inflation rates accelerate, they naturally will however tend to depress real wages and they will also tend to reduce the population’s real money balances – the money that they have becomes worth less than it was and hence their ability to spend is compromised. Moreover, history suggests that higher rates of inflation tend to encourage people to save more. Together, these various effects should serve to bring demand back down (i.e. to create a leftward shift in the demand curve) and this will bring with it the prospect of inflation abating after some degree of lag (a lag that at a practical level is likely to be made worse by the fact that the CPI itself tends to lag the “real world” somewhat, thanks primarily to its treatment of rents and other imputed variables). In such a world, in which prices can rise and thereby squeeze real incomes and real monetary growth, then the period of higher inflation could indeed be transitory – although the period of transit can be quite long and there will be a period of stagflation as the economy slows before inflation moderates.

However, if the authorities were to react to the lack of real growth – and perhaps even the pressure on real wages – by adding yet more fiscal and / or monetary stimulus to the system (as they are usually prone to do), then it is likely that they will simply generate another bout of inflation given the still binding supply constraints within the economy. Indeed, it is also probable that by the second or even the third time around, people may start to expect that greater stimulus equates to yet more inflation and, as expectations rise, the higher inflation rates will tend to appear sooner and more aggressively than in the prior cycle.

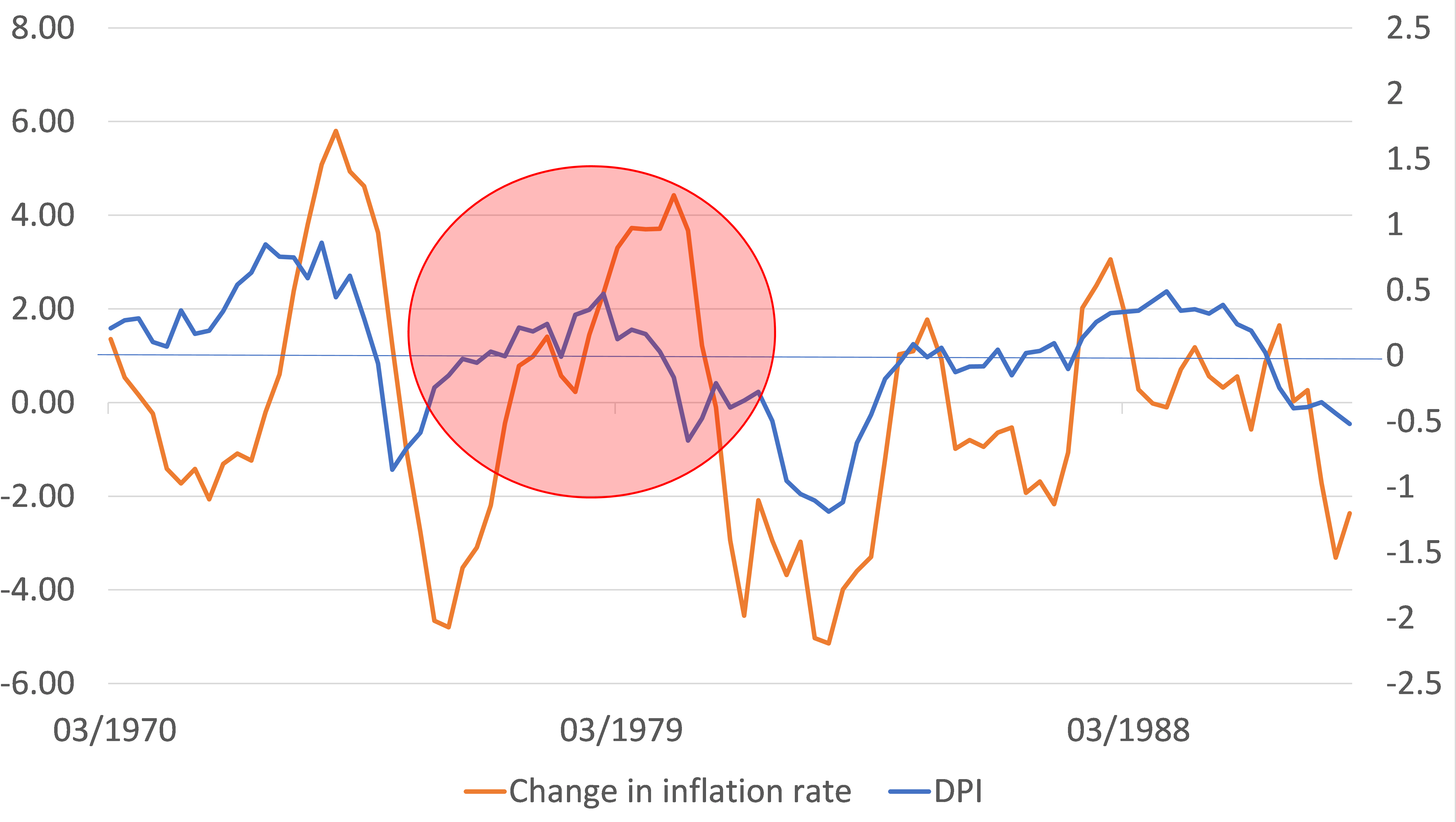

This was certainly the West’s experience in the second half of the 1970s – having been caught out by inflation in 1973 people were prepared for it when policy eased again in 1975/6 and certainly in 1978/9. The inflation / growth trade off was poor in 1972-74 but it was even worse in 1978/79.

USA: Demand Pressure Index

with headline CPI, DPI, RHS; change in annual CPI inflation LHS

So far, the financial markets seem to have taken the recent “shock CPI data” from what is fast becoming a large number of countries in their collective stride, not least we suspect because the central banks are steadfastly refusing to validate inflation concerns. But, the fact remains that the binding constraint on global real economic activity at this time is the system’s physical supply capacity, not the level of nominal demand. Therefore, by definition, we are in a world of excess demand that the market is attempting to choke off by charging higher prices. This is a perfectly “natural process” that will result in still higher rates of inflation in 2021H2.

If no further action is taken by the authorities, then over time these higher prices will reduce people’s real incomes, deflate their real money balances, and even encourage them to save more, with the result that demand will weaken and inflation rates will moderate in early 2022. Fixed income markets may yet take (modest) fright at the higher inflation data in the near term but they probably would (remain) be backstopped by the thought that the inflation would be transitory.

However, we must also acknowledge that if policymakers react to the weaker growth outlook and the mounting pressure on real wages (particularly within the lower income deciles) that we are currently witnessing by providing more demand-side stimulus, then we suspect that private sector inflation expectations will jump and that any increase in nominal demand in 2022 will then largely occur within the price rather than quantity term. We would then be in a world of permanently higher inflation that would be fundamentally poisonous to the debt markets.

In summary, we are expecting higher inflation in the near term, then a pause in inflation before a policy-driven trend acceleration in 2022-2023 and we suspect that it will be the latter that may prove to be the biggest risk to bond markets.