Understandably much of the popular market commentary has centred around the possible “Repatriation Trade” and in particular is has focussed on possible flows out of the UST by foreign investors. There have also been stories of some selling of US equities and private credit instruments, all of which sound quite alarming given the USA’s hefty net Foreign Liabilities Position and reliance on foreign capital to cover its deficits. As we noted earlier this year in our regular reports and client presentations, it is certainly true that the Rest of the World owns considerably more of the USA than the USA owns in the Rest of the World. This is the result of the US’s persistent current account deficits and the relative outperformance over recent years of US assets.

Unfortunately, although we have some official “stock data” concerning the size of the various assets and liabilities that may be involved, in a purely practical sense, it is virtually impossible to know who owns what and what it would in fact be worth if investors were ever to attempt to realize the assets “in size”.

We certainly doubt that the Japanese bank that recently got “caught” in the US Treasury basis trade had any inkling just how much it was about to lose before it happened, or that the market let alone the statisticians knew what its true exposure to the trade was before it unwound. Of course, very similar dynamics unfolded during the GFC; no one knew just how much exposure Credit Agricole had to CDOs (and what they were truly worth) until the US subsidiary “blew up”; and the German banks’ exposures to mortgages were of course very very much larger than the data suggested before the event. We suspect that too heavy a reliance on the stock data would be unwise; and it will of course be the flows that matter to markets and prices.

Interestingly, data that we employ to monitor US liquidity trends suggests that the US’s basic balance deficit (i.e. the sum of the current account deficit and the long-term capital account balance - which includes equity and fixed income market flows, as well as Direct Investment Flows) is running at a circa $100 billion per month rate, roughly the same as the run rate as the current account deficit. This in turn implies that the US long term capital account balance must in fact be close to zero at present, which itself tells us that any repatriations of capital by foreign long-term investors in the USA is currently being matched by sales of foreign assets by US residents.

It could be that there are large repatriations of capital occurring from the USA that are being matched by equally large US repatriations of capital but we suspect that in truth the capital flows have simply “frozen” with relatively modest flows occurring in both directions. This of course does (still) simply that the current account deficit is no longer being funded by long term capital flows (as we shall see, it has instead been funded by large short term credit flows within the banking system so far this year) but we are not yet seeing signs of true capital flight despite the news flow and “stories” that are circulating.

This is not the first time that we have witnessed such a divergence between opinion and data. At its heart, the Asian Financial Crisis was an “unfunded current account deficit crisis” – most of the countries within the Region possessed current account deficits of circa 6% of GDP ahead of the crisis and, during the early / mid 1990s, these deficits were funded these deficits predominantly with short term credit (i.e. “carry trade”) monies. This process, although inherently unstable, persisted for a surprisingly long time, most likely because monetary conditions in the rest of the world remained surprisingly accommodative for much longer than they should have done…

However, when the flow of credit was finally interrupted, the current deficits soon became unfunded and local borrowing costs soared. The higher rates and also a drying up in credit supply then caused the economic catastrophe that in turn led to the currency & financial crises that gripped these by then highly indebted economies. Indeed, the high real rates / crises led to a veritable collapse in domestic demand, which – by no coincidence - then led to the rapid closure of the current account deficits – and even emergence of surpluses.

Interestingly, although many of the short-term credit investors did manage to escape (- primarily via the simple expedient of not rolling over claims - and some even succeeded in riding the inflows then shorting the currencies), very few long-term investors (i.e. the investors in regional equities and the fledgling bond markets) were able to repatriate their monies before the crisis struck.

During the crisis, asset prices collapsed so rapidly that some markets virtually stopped trading. At this point, had investors sold, the amount that they would have realized would have been minimal so instead they simply “went over the cliff” with the Region.

The principal lessons here for us are (were) that true capital flight tends to be quite rare – markets stop it with sometimes drastic domestic price action – but that unfunded current account deficits within highly indebted economies can nevertheless be incredibly destructive. Foreign investors don’t have to flee – they merely need not to turn up to cause significant stress.

In the paragraphs above, we indicated that the US current account deficit has been funded not by inflows of long-term capital, but rather by short term “banking system” flows. The weekly monetary statistics have revealed that there has been a marked divestment by US banks from offshore markets over recent months. At one level, this implies that there has likely been a significant tightening in global monetary conditions, and in particular we are concerned that this will impact the availability of trade credit in certain areas, most likely in Asia Pacific.

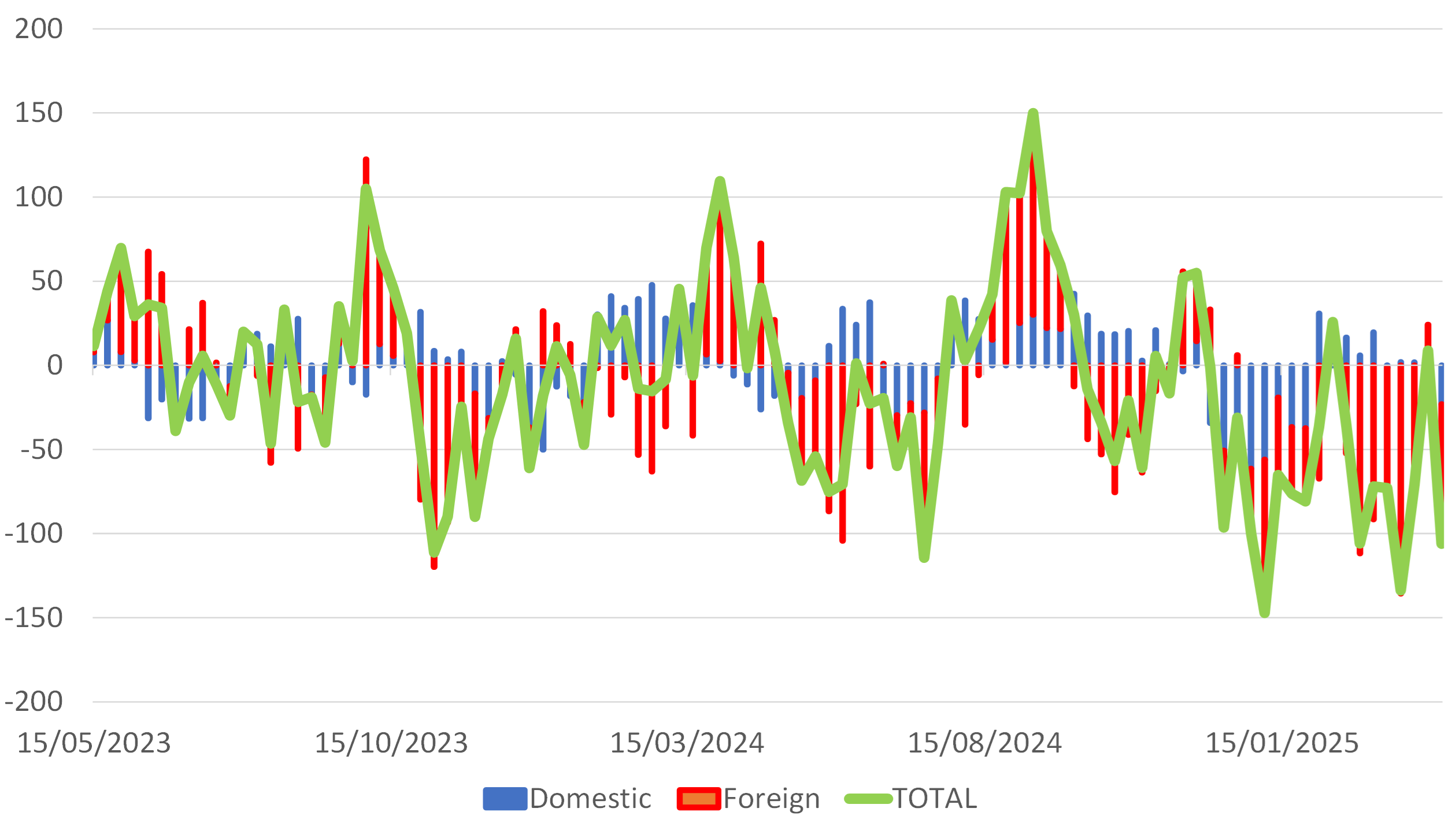

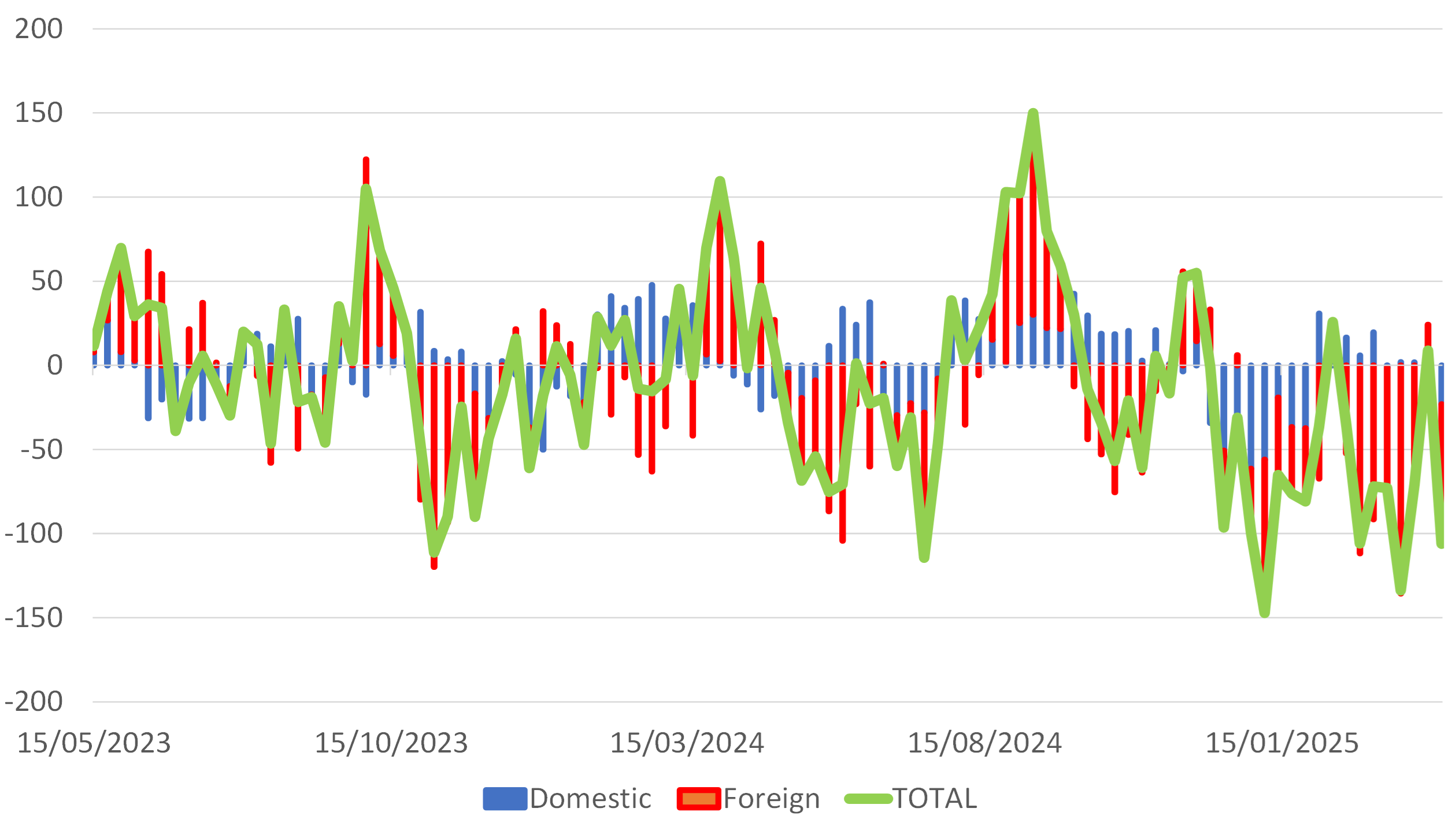

USA: Net Bank Credit to Non Residents

USD billion over 5 weeks, eastimated

USD billion over 5 weeks, eastimated

We suspect that it was these repatriation flows by US banks – that seem to have started well before the Inauguration – that funded the US deficit and thereby supported the US towards the end of last year and the beginning of this year. Of course, repatriation flows are finite by their very nature and we must be coming to the point at which the US banks will be running out of assets abroad that they can bring home. This exhaustion may be a big part of the recent dollar softness.

Meanwhile, there are clearly foreign bank funds that could now be repatriated (but which in all probability haven’t been repatriated yet). It is very possible that these repatriations could begin at a time during which the US banks are running out of foreign assets to sell, with the result that the US could face itself facing not only a (modest) basic balance deficit but also a sizeable short-term capital account deficit. At this point, its Balance of Payments could begin to resemble in character that of Asia during 1997 (the relative numbers compared to GDP will be smaller but the absolute numbers will of course be very much larger…). If this were to be the case, then we could expect credit supply trends within the economy to deteriorate quite sharply.

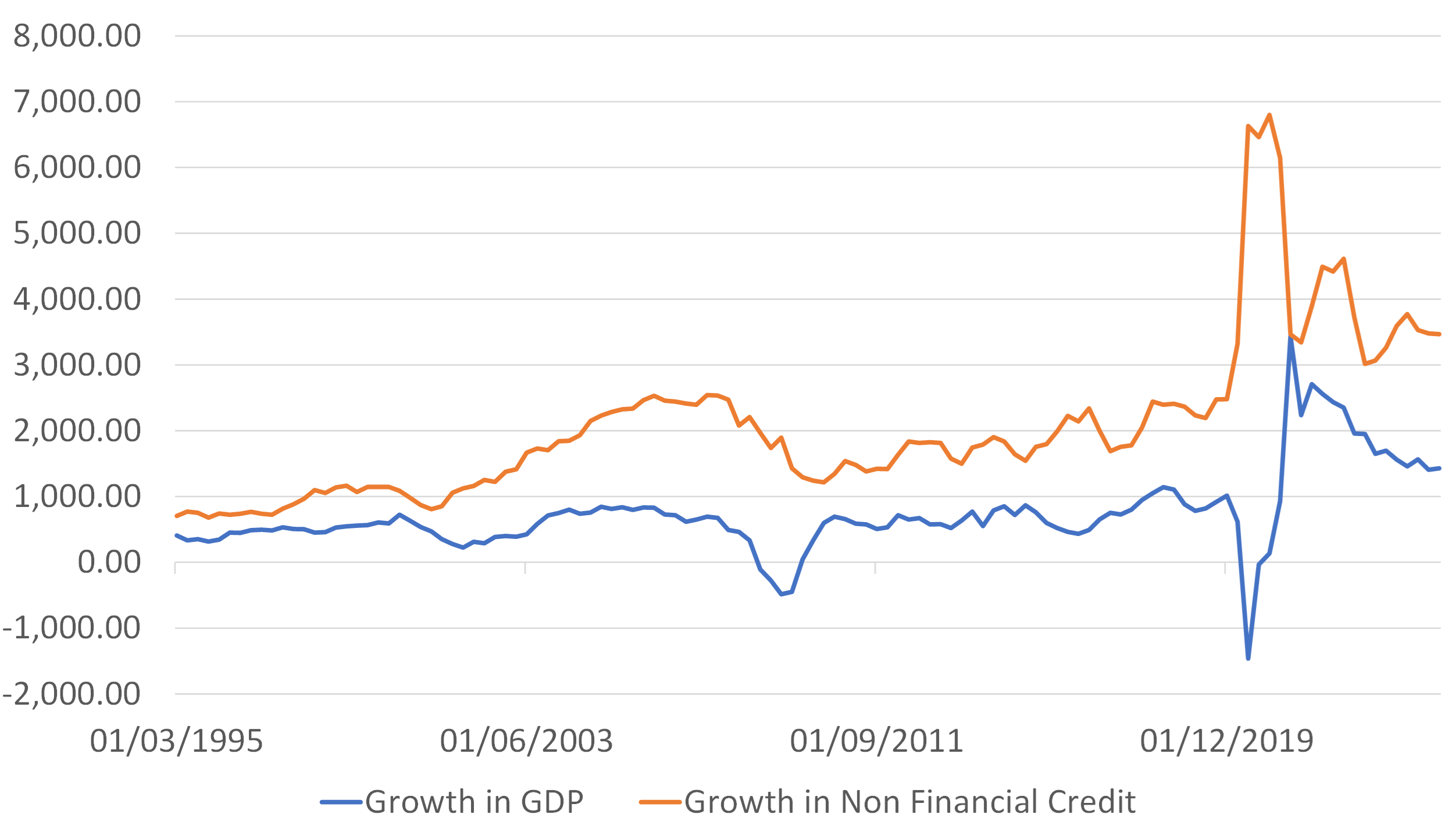

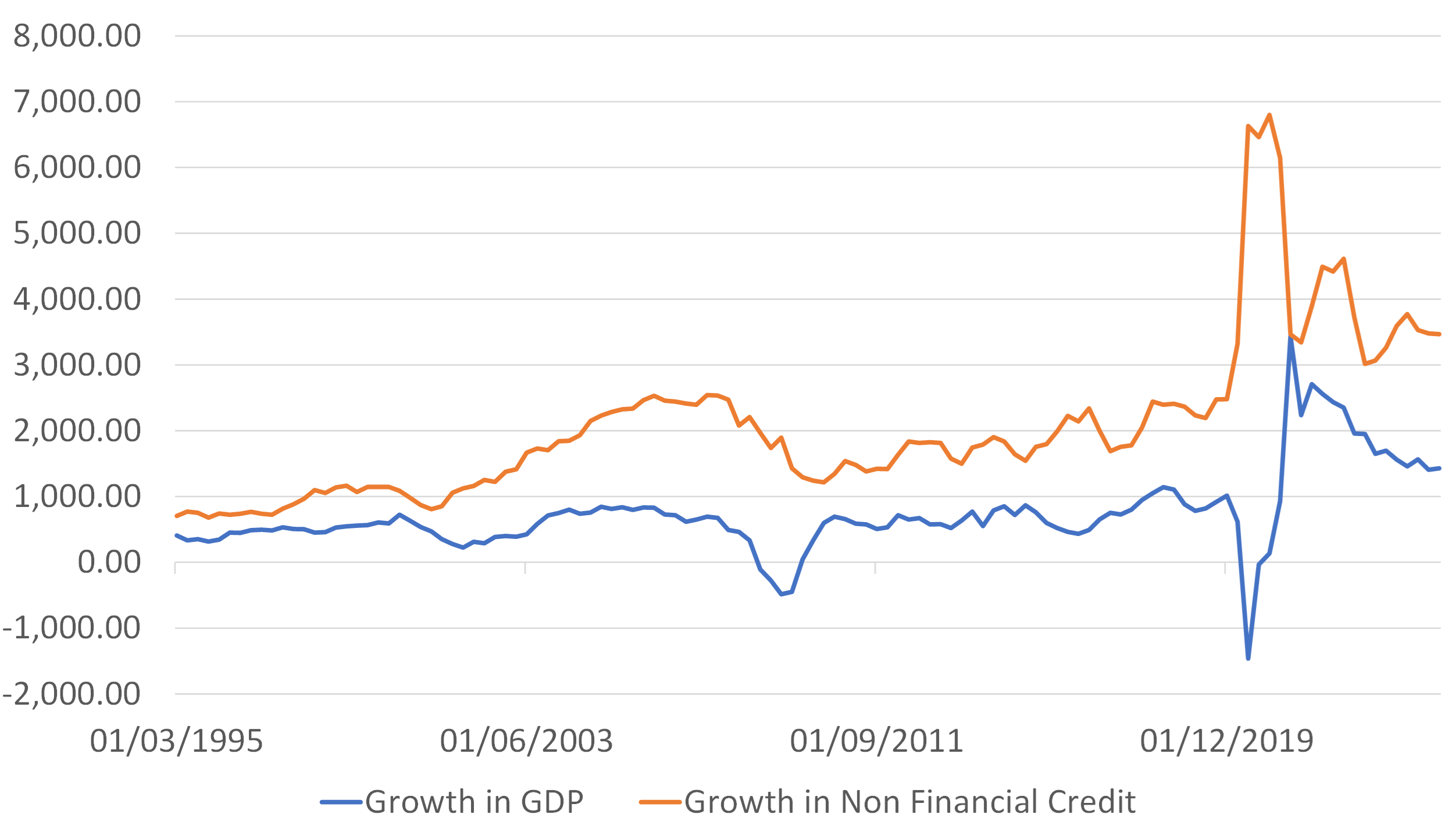

As we have remarked many times before, the US requires considerable flows of credit both in the public sector and in the private sector (although much of the latter has been hidden over recent years simply because much of the official data fails to capture the private non-bank channels). However, even the official data reveals the economy’s “credit dependency”.

USA: Debt Growth and Growth in Nominal GDP

USD billion over rolling 4Q

USD billion over rolling 4Q

As the Asian Crisis revealed, if current account deficits become unfinanced, then real borrowing costs will rise (particularly rates versus income expectations) and the supply of credit will be reduced. This unfortunate situation could take a time (i.e. a few weeks) to become apparent but if someone “large” attempted to borrow during the period, then the problems will likely be revealed.

This is why we are so concerned that, when the Federal Government starts to issue debt on a net basis again in a few weeks’ time, yields could rise abruptly and private sector borrowers (including within the financial system) will be crowded out unless the authorities find a new QE-like way to monetize the deficit.

Clearly, the ongoing talk of changing bank capital rules vis-à-vis their UST holdings is preparing the ground for the latter to occur (and the pressure on Chairman Powell probably falls into this category as well) but we suspect that we could yet see a version of the “Asian Crisis Dynamic” later this summer as the government tries to raise funds against the background of an unfunded current account deficit – local yields will rise and the private economy will slow unless foreign capital is forthcoming in the meantime.

Rising yields and a slowing economy would of course unsettle equity markets, possibly quite severely. The slowdown would however address the current account deficit – weak domestic trends would likely shrink the deficit.

Longer term, we can assume that the US will find a way to ease / and monetize the deficit, which by rights should lead to some intense weakness in the true value of the USD. However, currencies are a relative game and we doubt that the US will be alone in pressing the “monetary panic button” at that point. Late 2025 therefore become a period of widespread debt monetization, something that financial markets might welcome for a time but which would ultimately be inflationary for 2026.

Disclaimer: These views are given without responsibility on the part of the author. This communication is being made and distributed by Nikko Asset Management New Zealand Limited (Company No. 606057, FSP No. FSP22562), the investment manager of the Nikko AM NZ Investment Scheme, the Nikko AM NZ Wholesale Investment Scheme and the Nikko AM KiwiSaver Scheme. This material has been prepared without taking into account a potential investor’s objectives, financial situation or needs and is not intended to constitute financial advice and must not be relied on as such. Past performance is not a guarantee of future performance. While we believe the information contained in this presentation is correct at the date of presentation, no warranty of accuracy or reliability is given, and no responsibility is accepted for errors or omissions including where provided by a third party. This is not intended to be an offer for full details on the fund, please refer to our Product Disclosure Statement on nikkoam.co.nz.