During the 1980s, the favourite worry for most economists – or Cassandras - was always deficits, be they fiscal or current account deficits (and the USA of course had both throughout the 1980s). However, despite the economics professions’ often dire warnings, the deficits rarely seemed to ‘matter’ to markets from the late 1980s onwards. They had of course mattered a great deal in the 1950s and 1960s – when countries suffering deficits found it hard to maintain their currencies’ exchange rates within the Bretton Woods system - but once the world moved off currency standards and defeated inflation, the deficits appeared to cease to a constraint on policymakers or markets.

Since then, there have been occasional ‘flirtations’ with trade and deficit reduction policies but in reality we suspect that few people within the markets have really worried about either the size of the US budget deficit, or the US trade deficit and its corresponding EZ / Asian surpluses, just as it has generally not been ‘right’ from a market perspective to worry about often large corporate sector financial deficits (i.e. the USA in the late 1990s or China since the early 1990s). For most of the 2000s, it was even ‘safe’ to ignore the huge US (and UK, Spain, Ireland, Iceland etc etc) household financial deficits. Following the GFC, markets occasionally paid some attention to fiscal deficits, but even this attention had a rather limited span…. For most of the last thirty years, it seems that deficits of any form have not really mattered, or at least not for very long.

The bottom line, as we see it, is that once ‘Global Inflation’ was contained during the early / mid 1980s, central banks – including those from countries that would run large deficits – have been able to ensure that the world has been operating against a background of almost perpetually soft budget constraints. Indeed, it seems that credit has nearly always been available to seemingly almost any borrower (including those that had defaulted before - Argentina springs to mind here) and as a result the way to make money seems to have been to borrow more, both in the real economy (even if you did not really have the cash flow to support the borrowings…) or within the financial sectors. In the US, the process was given both implied funding and even credibility by Alan Greenspan’s seemingly obsessive efforts to ensure that the financial system could absorb virtually any amount of risk so that there never could be binding ‘budget constraints’.

Hence, we have ended up with highly leveraged economies that are often skewed to entities that do not necessarily make much (hence the weak productivity growth of recent years) but exist by borrowing huge amounts of money, sometimes merely to support their own share prices.

This is of course all perfectly rational with the context of a world of uber soft budget constraints, why bother making anything when you can just borrow money and announce a ‘winning concept’? At this point one is reminded of the famous prospectus from the time of the South Sea Bubble that promised “a company for carrying on an undertaking of great advantage, but nobody to know what it is.” Last year, it almost seems that similar blank-cheque companies proliferated on Wall Street as a record number of special purpose acquisition vehicles came to the market.

Of course, once such a situation becomes ‘accepted as being the norm’ and adopted by consensus, it tends to be viewed as sensible and valid, if for no other reason than “it is better for reputation to fail conventionally than succeed unconventionally” (J. M Keynes), or in today’s world it is better to match the index than risk falling behind. As a CIO friend recently remarked, “clients don’t thank you for losing less money than the market when it falls, but they more often than not fire you for making less money when it rises”.

Of course, the conventional wisdom can always be shattered if hard budget constraints are imposed and thereby put an end to the ‘schemes’ by demanding a closure of deficits and imbalances. The faith and consensus acceptance of both the Asian and Celtic Tiger Myths was shattered in the 1990s when the countries found themselves facing a lack of foreign funding, as was Iceland’s rather crazy boom of the 2000s. When it became apparent in 2007 that the maths simply didn’t work in the mortgage derivative markets, US households found that not only did their deficits matter but that they needed to close them quickly, mainly through the simple expedient of spending very much less….

Moving from a soft budget constraint world in which it pays to be leveraged rather than a saver, to a world of hard budget constraints and a focus on cash flow is usually traumatic for most of the actors concerned – be they borrowers, lenders, or vendors. Moreover, the longer that budget constraints have been soft, the larger the imbalances, debt ratios, and dependency on credit tend to have become. Consequently, central banks will only risk creating hard budget constraints when they absolutely have to (although on occasion they do create them by accident).

In reality, we suspect that only four forces are ‘big enough’ or important enough to force the major economies into hard budget constraints: a mistake or ‘flaw in the machine’ as occurred in the GFC; the return of consumer price inflation that cannot be ignored; geopolitics or even conflict; or a seismic shift on the political environment.

On a number of occasions over recent years, a number of “accidents” have nearly occurred that might have given us a fatal flaw in the machine – the funding crises in late 2018 and September 2019, and the impact of Covid-19 on the bond markets last March came close but in each case disaster was avoided in the last moments. Central Banks seem particularly keen to avoid such eventualities.

Ultimately, we firmly believe that inflation is returning to the Global Economy, but this is unlikely to be a factor in the next few months, particularly given the arrival of a second wave in the virus. Unfortunately, we can also see that the world is drifting towards greater geopolitical risks. Certainly, we would not underestimate the potential for a Sino-US clash to move away from a few trade tariffs to something much more damaging, such as a capital account war or tense confrontation over Taiwan.

Finally, the global political environment has been starting to look rather unstable for a number of years, as increasingly narrow groups of incumbent elites – who quite simply have not done much to raise real incomes of the bulk of their populations over the last decade - come under pressure from what the media rather dismissively describe as ‘populist parties’.

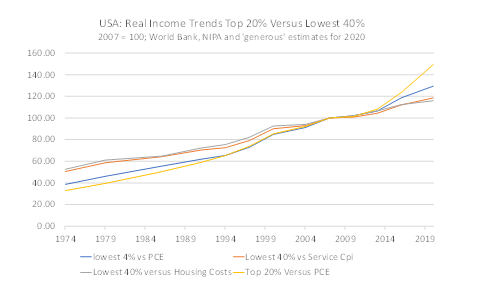

We estimate that the top 20% of the US income distribution command 47% of the country’s income and that, compared to the PCE deflator, their incomes have increased by 40% since the GFC. The lower 40% of the income distribution receive circa 27% of national income and in real terms this group’s income has increased by 30% relative to the aggregate PCE deflator. However, relative to service prices (i.e. items that they will tend to consume ‘every’ day), real incomes in this group are only up by 19% since the GFC, and by 15% relative to housing costs.

Events on Capitol Hill last month were of course as shocking as they were unjustifiable, but clearly millions of ordinary US voters did in some sense vote for ‘genuine change’ in the status quo, not just in 2016 and in 2020 but also 2008 and 2012….. It remains to be seen how the Biden Administration will balance the sometimes-competing demands of its own supporters. Chairman Powell has already signalled that even the Fed is having to think about what the median voter wants to see.

In summary, it seems to us that there is at present little or no chance that the Fed or any other central bank will deliberately seek to impose hard budget constraints on their economies while Covid-19 rages. Therefore, the leveraged boom in asset prices should continue in the near term (unless the Global Geopolitical System really does flare up) and the US should continue to bleed dollars into the rest of the World. But, once the virus is finally contained, and / or inflation resurfaces (or most likely both occur), we may find that the era of soft budget constraints comes to at least a temporary end.

Consequently, we would suggest that one should stay long risk assets and short the USD until budget constraints tighten, but when they do tighten, we can assume that the one asset that will be in short supply will likely be the cash that will be necessary to unwind the leverage boom.

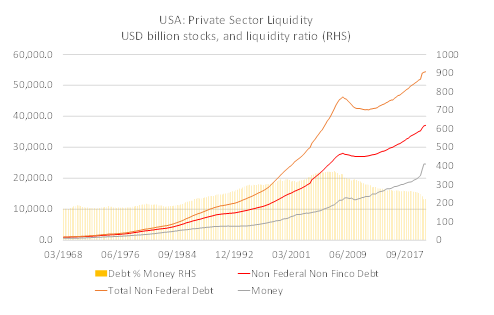

More positively, and in what may prove to be an important ‘difference this time’, it is interesting to note that at least the US Private Sector’s liquidity ratio is arguably the best that it has been for almost 40 years as a result of last year’s boom in monetary growth. Although the stock of debt continues to dwarf the stock of money that can be used to repay it (hence our comment above), the relative size of this ‘solvency gap’ is much lower than it was in 2008/9 – thereby providing more evidence that the 2020/21 experience is likely to be more like a 1950s-1970s inflation cycle than a 2000-2010s deflation cycle……

Disclaimer:

The information in this report has been taken from sources believed to be reliable but the author does not warrant its accuracy or completeness. Any opinions expressed herein reflect the author’s judgment at this date and are subject to change. This document is for private circulation and for general information only. It is not intended as an offer or solicitation with respect to the purchase or sale of any security or as personalised investment advice and is prepared without regard to individual financial circumstances and objectives of those who receive it. The author does not assume any liability for any loss which may result from the reliance by any person or persons upon any such information or opinions. These views are given without responsibility on the part of the author. This communication is being made and distributed in the United Kingdom and elsewhere only to persons having professional experience in matters relating to investments, being investment professionals within the meaning of Article 19(5) of the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000 (Financial Promotion) Order 2005. Any investment or investment activity to which this communication relates is available only to and will be engaged in only with such persons. Persons who receive this communication (other than investment professionals referred to above) should not rely upon or act upon this communication. No part of this report may be reproduced or circulated without the prior written permission of the issuing company.