Since 1995, the price of an ‘average’ restaurant meal in the USA has increased by 102%. Since 2009, the price of a meal has increased by 25%. Hotel prices have increased by 50% since 1995, and by 30% since the GFC (if we exclude the Covid-19 period). A haircut costs 25% more than 2010, while the price of an entry-level Ferrari has gone from US$140 000 in 1995 to between US$270k and US$300k today, although even the prices of Maranello’s finest have not kept pace with house prices in the USA despite the Great Recession. There has clearly been plenty of inflation in the USA – and elsewhere - since 1995 and of course even since the GFC.

However, while the price of a Ferrari or Aston Martin may have doubled, the price of an average family car is only 8% higher than it was in 1995. In 1995, one in eight cars sold in the USA was produced abroad, today it is one in four (or three in some months). Since 1995, the price of a TV set has dropped by more than 90% on a quality-adjusted basis (although we might argue that the quality adjustment might be rather overdone when we are trying to find an actual channel…). US TV production has dropped by 60-70% since the 1990s.

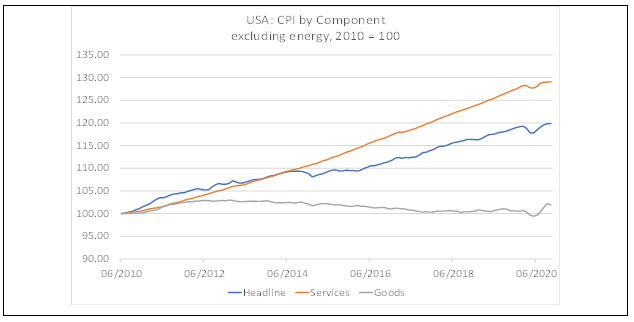

In reality, the Post 1995 history of inflation has been one of two stories, namely significant inflation in certain services, non-traded goods, and certain other products in which there are barriers to entry (such as the requirement for an ‘okay’ 100-year motor racing heritage…), and deflation in the traded goods and other sectors that have witnessed rising import penetration.

If you were lucky enough to work in one of the first groups, then your incomes will have tended to rise, but if you were working in the second group then times have been harder with weak income growth and declining employment levels. Hence, we have witnessed the politically destabilizing rise in income inequality, and regional concentrations in economic growth. We might also add that the second group tend to witness faster rates of productivity growth than the former (hand-built cars versus robotics…) and so we might also seek to explain the weaker trend rate of productivity growth in the West over recent years on this change in the economic structure.

The headline consumer price index so beloved by policymakers is in reality little more than a slightly random mathematical construct, namely a weighted average of the goods and services in our first group, and the prices of goods within the second group (roughly two thirds & one third respectively). Consequently, in a mathematical sense, the deflation in traded goods prices since the mid-1990s has offset the inflation in services and thereby provided the illusion of price stability. Indeed, inflation has tended to be ‘a little low’ at a headline level and as a result central banks have, more often than not, provided accommodative monetary conditions since the mid-1990s. The impact of their policy settings on real interest rates within these two very different sectors has however been interesting:

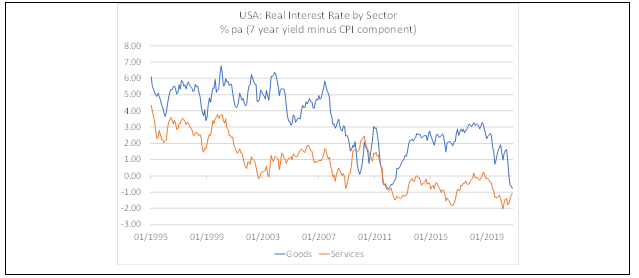

In the service sectors, real interest rates were half of those in the goods sectors during the late 1990s. Since 2000 they have rarely been over one percent and, more often than not, they have been negative. In the goods sectors, meanwhile, real interest rates have at times been much higher and rarely below one percent. Naturally, this situation reinforced the process of relative inflation in non-traded goods (and we would include housing / accommodation as perhaps the ultimate non-traded good), and relative deflation in goods prices.

Indeed, absent some exogenous shock, we could assume that non-traded goods prices should inflate both absolutely and relative to goods prices ad infinitum under this model, to the ongoing long-term discomfort of value investors. Meanwhile, the relative weakness in goods prices should place a cap on bond yields.

Of course, this model also implies that the economy’s basic pricing structure will continue to move away from its equilibrium, thereby implying that the economy’s basic structure will become ever more distorted, to the detriment of much of its population. For those looking to properly explain the rise of ‘populism’, one needs to look no further than these charts – highly distorted economies tend to produce unequitable and unhappy societies.

Of course, if the deflation in goods prices could be attributed to “efficient fundamentals” and it was the result of a genuine price signal, then one might argue that the process was justified and even economically efficient on a global scale. However, the decline in import prices has not, we would argue, been the result of conventional economic efficiency. Instead, it has been the result of the nature of the model used by the North Asian economies.

It is of course entirely right and proper that the North Asian economies should have developed and improved their own standards of living but what concerns us is that the model that they have used – which may well have been entirely right for them – has not been compatible within the confines of the same WTO trading system as the rest of the world’s profit maximizing model. The West’s model is of course centred on profit maximization and the price mechanism but in Asia the combination of single party states and a need to produce rapid economic and employment growth has resulted in the countries employing employment maximizing strategies, even at the expense of profits, cash flow and their debt ratios.

However – and rather crucially – we have noted that the Asian business model may be beginning to evolve. Indeed, following the banking & financial crises of the mid-1990s we noted that Japanese companies changed their behaviour towards being more sensitive to their cash flow, and we can also observe that Korean companies began to change their behaviour following the credit supply problems that were implicit within both the Asian Financial Crisis and also the GFC. More recently still, China’s leaders have talked about the need to reduce the country’s reliance on debt and raise its incomes cash flow through import substitution and other measures (part of their Fortress China / Economize on USD borrowings strategy).

It therefore seems to us that the Covid-19 Crisis may have hastened the ‘wind of change’ in Asia towards a more cash flow / profit centred model, a situation that could signal the end of its export price ‘subsidies’. This would certainly offer a rather convenient explanation for just why Asian Export Prices seem to be rising somewhat ahead of schedule at this time. Just as the West has been embracing Eastern-style never-ending-soft-budget constraints in the Pandemic, Asia seems to be moving the other way.

Indeed, we do find it somewhat interesting that, despite all that has occurred this year, we have ended our scheduled production run with the same thought that we ended with last year, namely that there is a growing risk of imported inflation from Asia generating a tightening of effective monetary conditions in the USA during the second part of the coming year. Indeed, it is interesting to note in our earlier chart that real interest rates in the US goods sectors are today falling even as they rise in the service sectors.

If the price of importing from Asia is indeed set to rise as tariffs, higher transportation costs and a change in the Asian Corporate Model all raise the costs of sourcing goods from abroad, then we can assume an inflation surprise for markets as early as mid-2021. Such a shock could come sooner if the current highly accommodative US monetary conditions continue to undermine the external value of the USD. Clearly, this is not something that the Fed was expecting at the time of the Jackson Hole conference, when it promised ‘never’ to raise interest rates.

The Federal Reserve may of course simply decide not to react to any inflation surprise, or may well chose to react ‘late’ to the event. Under such a scenario, we might expect the long end of the curve to sell off / curve steepen once Treasury issuance picks up again from mid-2021 onwards, and for this to take some of the ‘heat’ out of asset price and even service sector inflation rates.

However, if the Fed were to move more aggressively to control inflation / support the dollar in a timely fashion (perhaps even announcing such a move at the Congressional Finance Committee testimonies), then we could imagine a further rise in real interest rates in the service sectors and perhaps even some deflation in asset prices. Such an event might create some stresses for leveraged ‘speculators’ and for those worried about the value of 401Ks etc, but higher real rates in the service sectors than within the goods markets might at least bring about a long overdue rebalancing of the economy.

Disclaimer:

The information in this report has been taken from sources believed to be reliable but the author does not warrant its accuracy or completeness. Any opinions expressed herein reflect the author’s judgment at this date and are subject to change. This document is for private circulation and for general information only. It is not intended as an offer or solicitation with respect to the purchase or sale of any security or as personalised investment advice and is prepared without regard to individual financial circumstances and objectives of those who receive it. The author does not assume any liability for any loss which may result from the reliance by any person or persons upon any such information or opinions. These views are given without responsibility on the part of the author. This communication is being made and distributed in the United Kingdom and elsewhere only to persons having professional experience in matters relating to investments, being investment professionals within the meaning of Article 19(5) of the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000 (Financial Promotion) Order 2005. Any investment or investment activity to which this communication relates is available only to and will be engaged in only with such persons. Persons who receive this communication (other than investment professionals referred to above) should not rely upon or act upon this communication. No part of this report may be reproduced or circulated without the prior written permission of the issuing company.