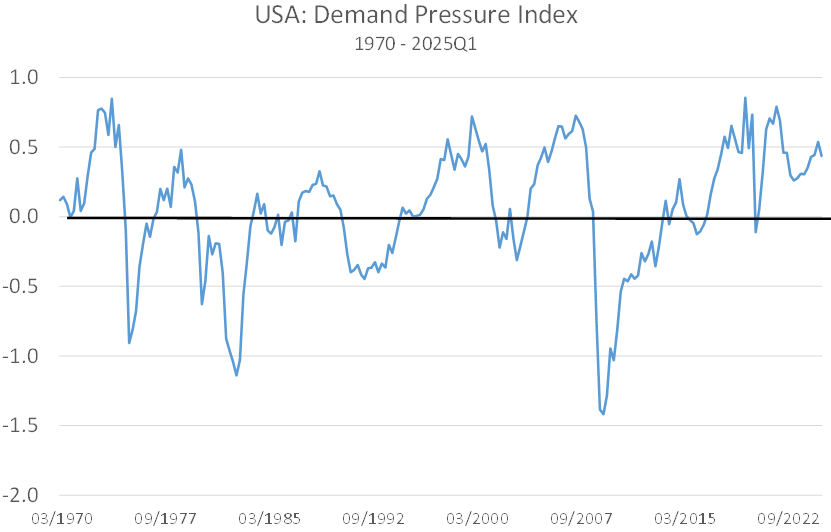

One hundred and fifty-three quarters have passed since the rather “political” Alan Greenspan was appointed the Chairman of the Federal Reserve. According to our Demand Pressure Index, which seeks to provide a better estimate of the output gap in the economy, the economy has been run “hot” with positive demand pressure (i.e. demand exceeded sustainable supply) in ninety-nine of those post 1986 quarters. Prior to 1987, the index had been in negative territory almost as many quarters as it was in positive territory.

Theoretically, this persistently positive output gap situation should have been inflationary and we do find that, since Mr Greenspan’s appointment in February 1987, the PCE measure of domestic service prices has increased by a considerable 211%. Within this price index, we find that Healthcare prices have increased by 240%, spectator sports admission costs have increased by a whopping 350%, and restaurant meals by 215%. Admittedly, the headline PCE index has increased by only 140%, the arithmetical result of the more modest 48% rise in goods prices over the period.

The limited rise in goods prices was partly the result of hedonic pricing adjustments (a thorny subject in itself – a practice that was originally invented to hide the true cost to the Pentagon of nuclear weapons) but the primary reason for the relative lack of inflation in goods prices was of course the increased reliance on imported lower cost goods.

The reliance on imported goods to meet demand and (in effect) suppress headline inflation rates implied that the US has been obliged to run persistent current account deficits. Since 1987, the cumulative current account deficit has amounted to almost $16 trillion. A current account deficit implies that the country must attract foreign funding on a net basis, which is why the US’s net international investment position has deteriorated from a near balance during the 1980s to around minus 90% of its GDP last year (although we think that the true number may be more than minus 100% of GDP, if truth be told).

The other important implication of a persistent current account deficit is that the country haemorrhages income to the rest of the world (and here we are not only talking bot the US’s investment income balance within the balance of payments data). This is the primary reason that average real household wage incomes have “only” grown by 175% since 1986, despite the “hot economy”.

Of course, even this average data has been skewed by a limited number of households that have done substantially better (i.e. income inequality has increased markedly and median incomes have lagged the average data). Crucially, there have also been marked regional differences – only 14 States have experienced above national average rates of GDP growth since 1992 (Arizona, California, Colorado, Florida, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, N Carolina, S Carolina, S Dakota, Texas, Utah, Washington and Wyoming). In effect, US income growth has been concentrated in certain income strata and really only half a dozen physical locations – other states such as Illinois, Pennsylvania and Michigan look to have lost out to the haemorrhaging of incomes abroad. No wonder some states / voters support tariffs….

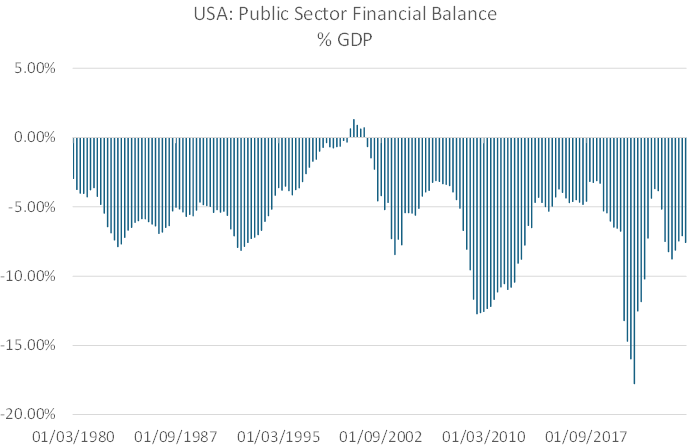

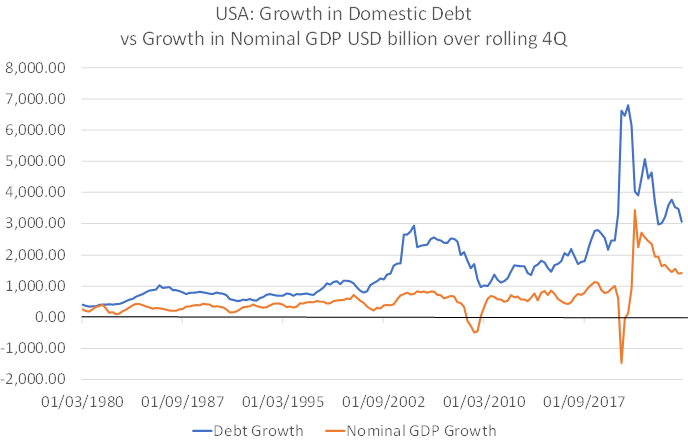

Maintaining economic growth in the face of this persistent loss of incomes has required accommodative economic policy settings – hence the ratchetting up in the fiscal deficit and also the Fed’s support of expansionary monetary policies. Interest rates have fluctuated over the period but in general credit growth within the economy has proceeded at rates far faster than nominal GDP growth, and monetary growth has also generally been faster than GDP growth. No wonder the financial sector did rather better than Mainstreet in this world.

Given its nature, the US’s post 1980s model possessed a number of vulnerabilities: changes brought about by domestic politics given the uneven growth; the ongoing requirement to source cheap imports (something that went wrong in 2000, 2007, 2018 and of course 2021/2); the ability to fund budget deficits (admittedly, this seemed easy with QE); the ability to keep the credit system expanding (only a problem when inflation appeared); and the ability to attract seemingly endless foreign capital on a net basis in order to fund the current account deficit (and implicitly to keep local real yields down). Ultimately, we would argue that the two most important necessary conditions required to keep the system working were access to cheap foreign goods and inexpensive foreign capital.

While the previous Administration probably exploited the model to the full, the changed political situation in 2025 has exposed a number of these vulnerabilities. Domestic politics have conspired to place tariffs on the agenda, and in so doing threated to create meaningfully higher import prices. The threat of inflation from this source has in turn made it difficult for the FRB to consider QE, thereby threatening the domestic funding of the budget deficit. Finally, souring international relations (again a function of changing domestic politics) risks curtailing the US’s access to foreign capital.

Above, we used the phrase “risks curtailing the US’s access to foreign capital” rather than has curtailed its access. We have constructed an estimate of the US’s long term capital account balance by attempting to reconcile the GDP current account data and the monetary data. We suspect that there is some degree of error in the data (but there always is in Balance of payments numbers…) but, perhaps surprisingly to some, we find that the US has continued to experience net capital inflows in most weeks since the Inaugeration. There is no net repatriation trade occurring at this time.

What we can observe in the chart shown above is that when the US asset markets are weak (in particular equities), then the Long-Term Capital Account is weak, and vice versa. What we cannot isolate is the causation – do capital outflows beget a weak market or vice versa? In practice, we suspect that the equations are simultaneous and very reflexive.

Crucially, we suspect that if US liquidity or news events create stronger US asset prices, the “FOMO-effect” causes foreign investors to engage, the capital account therefore improves, and this creates both stronger markets and more liquidity in the USA. This we suspect is what has occurred over recent weeks – the presumed capitulation on tariffs and a drawdown in the US government’s cash balances have created an environment conducive to capital inflows that has then sustained the markets. In short, Goldilocks – as the Post 1987 model seems to have become known by – has returned.

Quite possibly, this has occurred with the begrudging but probably now active encouragement of the Administration. We have described elsewhere how US GDP could decline by 3-5% if the vulnerabilities within the Post 1987 model were crystallized and, faced with that unappealing prospect, the Administration has clearly acted to cool the tariff-tennis, talked positively about maintaining economic growth, and moved to provide yet more fiscal stimulus (and harangued the FRB over monetary policy).

We suspect that Goldilocks is fickle. Bad news on tariffs, inflation, or general politics could yet unsettle markets and hence capital flows. Policymakers need to be very careful just what they say – and how they say it. However, the biggest threat to the return to the old model comes from the budget deficit, or rather the funding of the budget deficit.

If last year offers any guide to the fiscal accounts, then the Treasury should exhaust its cash balances / fiscal reserves during the second week of July. At this point, the Debt Ceiling will either have been raised and the markets will be facing the prospect of $500 billion of net issuance over the following 8 – 10 weeks, or the US will have to resort to a default. Neither would seem particularly positive options for the US Treasury markets – which are already struggling with refinancing issuance.

If rising yields then exposed the fragilities within the US real and financial sectors, as seems likely, then it would be highly likely that asset prices would weaken, foreign investors would temper they appetite for US assets, and the long-term capital account would weaken, thereby setting in motion a reflexive vicious circle that would likely see US yields rise and the dollar come under pressure mid-year.

At some point in this process, the pain within the system would undoubtedly force the authorities back to some form of QE (the noise level over supporting the long end – globally – has already been moved up a notch or three). If the US were to act alone, we suspect that the dollar would decline further at this point but we suspect that in all probability Europe, Japan and perhaps even the PRC would also be moving in the direction of more Quantitative Easing at that time, and currencies would become indeterminant vis-à-vis each other. Of course, any money printing on a global scale would ultimately reduce the value of currencies vis-à-vis “things”; another round of global QE would therefore be inflationary.

Disclaimer: The information in this report has been taken from sources believed to be reliable but the author does not warrant its accuracy or completeness. Any opinions expressed herein reflect the author’s judgment at this date and are subject to change. This document is for private circulation and for general information only. It is not intended as an offer or solicitation with respect to the purchase or sale of any security or as personalised investment advice and is prepared without regard to individual financial circumstances and objectives of those who receive it. The author does not assume any liability for any loss which may result from the reliance by any person or persons upon any such information or opinions. These views are given without responsibility on the part of the author. This communication is being made and distributed in the United Kingdom and elsewhere only to persons having professional experience in matters relating to investments, being investment professionals within the meaning of Article 19(5) of the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000 (Financial Promotion) Order 2005. Any investment or investment activity to which this communication relates is available only to and will be engaged in only with such persons. Persons who receive this communication (other than investment professionals referred to above) should not rely upon or act upon this communication. No part of this report may be reproduced or circulated without the prior written permission of the issuing company.