This may appear an odd question to ask given the recent slew of poor inflation data points that have been released but we suspect that “all is not quite as it seems” within bond markets, or even the global economy. First, the inflation story. It is our firm belief that the recent unwelcome news in inflation across much of the World is due to historical and structural factors. Years of under investment in commodity capacity is an obvious issue within the goods markets, but even some of the increase in service sector prices can be viewed as a bygone. For example, insurance premia are surging across the World (my own premia are up by 20% in the UK and a little more in NZ) and this is due to factors within the industry itself, such as the growing complexity of vehicles and the damage done to the insurers’ own capital positions by years of QE. Changing interest rates today will not resolve these issues.

Moreover, much of the inflation that we re witnessing at present is occurring in things that can be regarded as being “necessary for life” and as such the rising costs of these items imply tht we have less money available to spend on other things. Hence, these rising prices are deflationary for growth and they go some way to explain why consumer trends are weakening in the USA and elsewhere.

Consequently, we doubt that the “inflation story” is really what has been behind the recent rise in bond yields across much of the World. Indeed, we believe that there is something much more profound occurring within the debt markets.

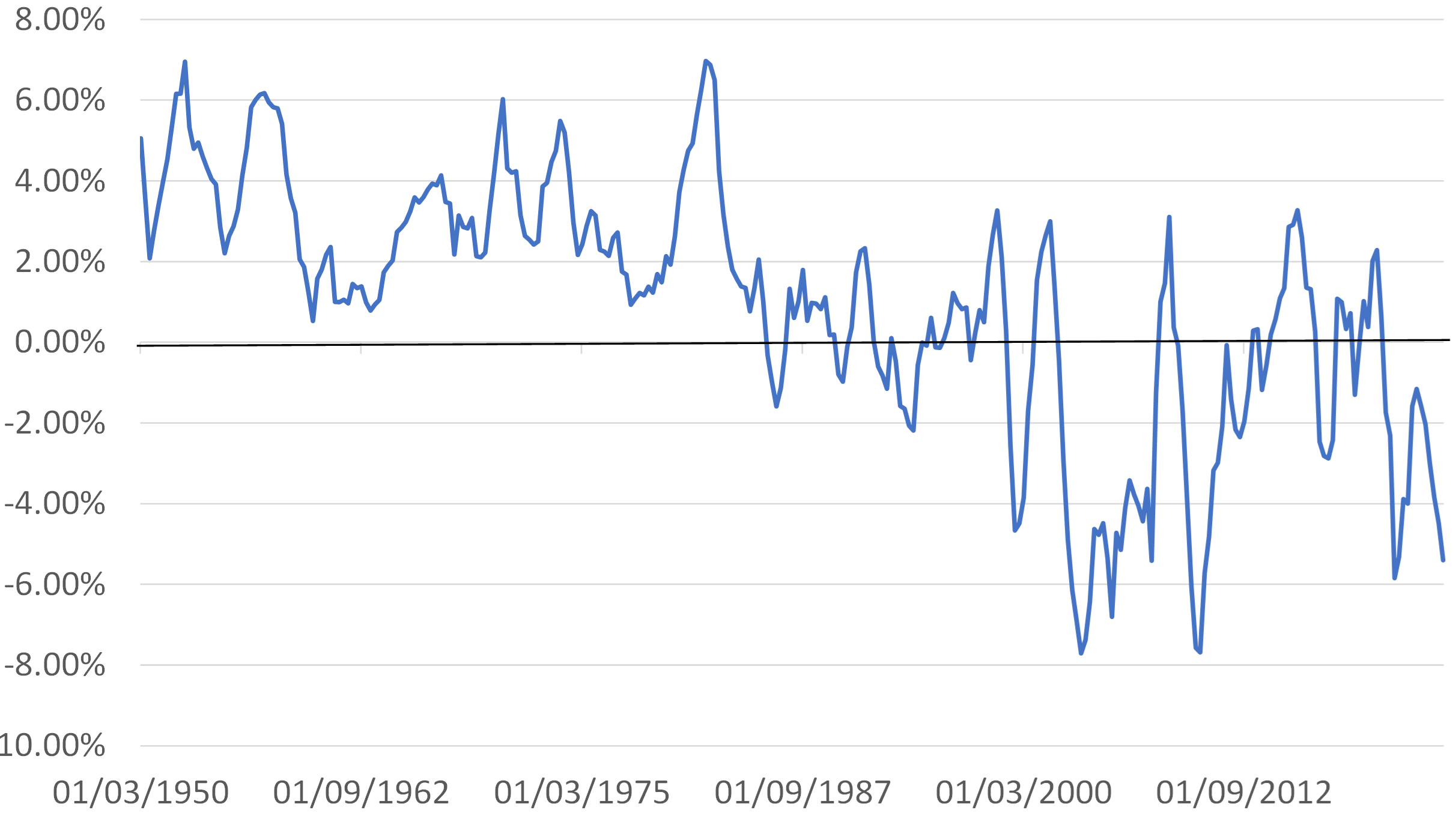

Today, the major G7 governments are borrowing substantially more than their domestic populations currently save. Only in Germany is this not the case, while in France, the UK, and Italy such behaviour appears de riguer. The US has also become a serial offender – it’s “Greater Public Deficit” (i.e. the household sector’s financial balance plus that of the government that serves it) stands at the equivalent of 5% of GDP.

Arguably, most countries are already borrowing “as though they were already at war” but they are only now finding out that the much-hyped “Peace Dividend” of the 1990s is reversing. What perhaps is surprising is that the rise in government borrowing relative to the flow of savings over the last 10 – 15 years did not appear to place sustained pressure on real yields, at least until now.

USA:Household Saving Minus Government Borrowing % GDP

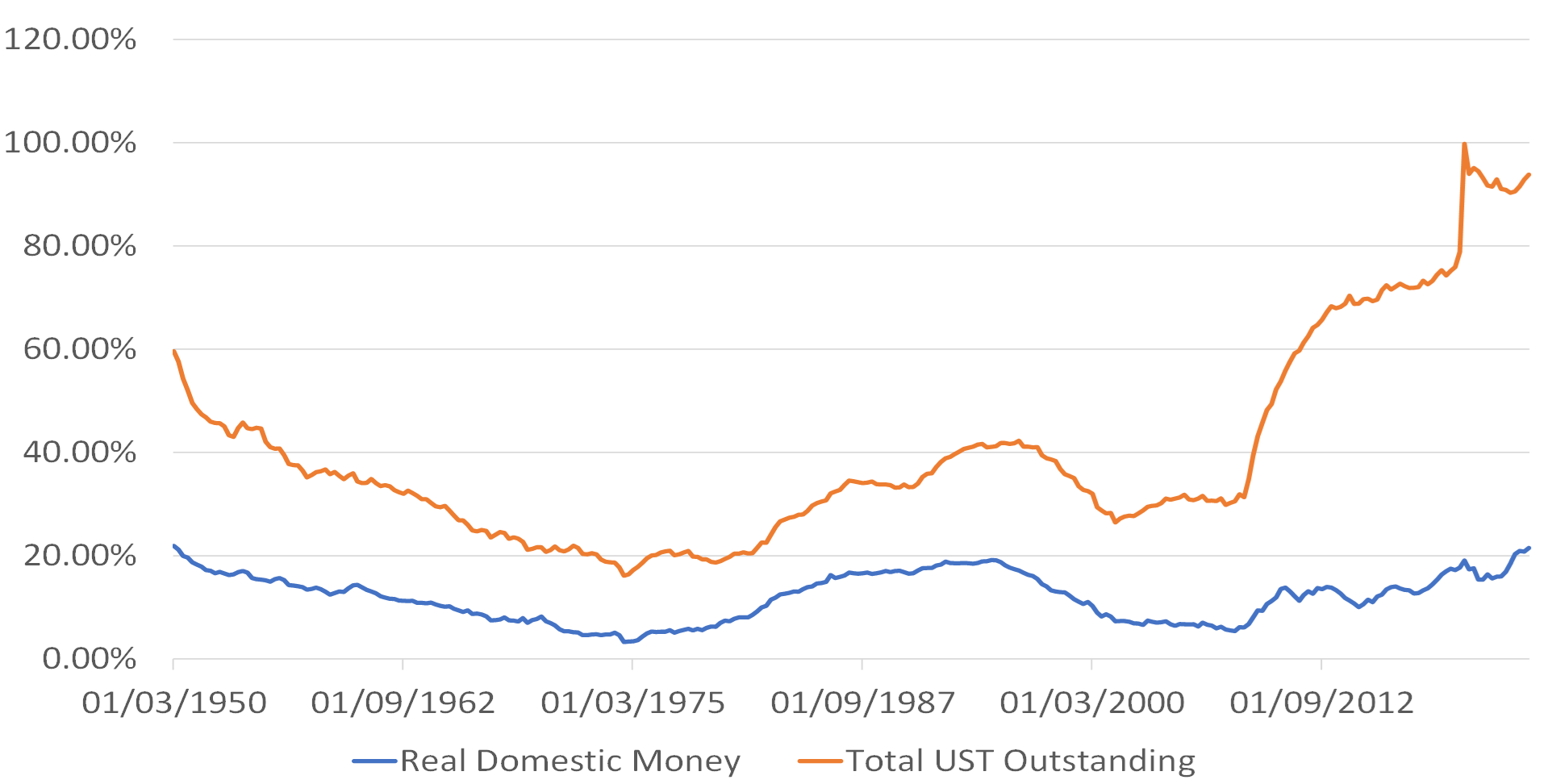

We believe that the lack of pressure on yields during the 20210s and early 2020s was simply because in the US – and elsewhere – real money investors were not called upon to fund the deficit. The US “real money sector” of end-user savers, pension funds, and insurers witnessed only a modest rise in its holdings of public debt relative to the size of the economy over recent years, while in other countries such as France the situation has been even stranger – the real money investors have been selling government bonds consistently since the GFC.

USA: Domestic Real Money Holdings of UST % GDP

USA: Domestic Credit Institutions' Holdings of UST % GDP

Conversely, the Federal Reserve, commercial banks, investment banks, and other leveraged institutions have seen their holdings of US government bonds rise by the equivalent of 25% of GDP since 2008. The Federal Reserve is of course the elephant in the room here through its serial Quantitative Easing, but banks & brokers also figure prominently, as do leveraged funds that require bonds for collateral purposes.

It should be remembered that when the Fed flooded the banking system with deposits during 2020/21, it (and the regulators) implicitly obliged the banks to park many of the incoming funds into government bonds. Similarly, the more speculation that the Fed encouraged via its words and deeds, the greater was the demand for bonds for use as collateral. That these institutions continue to hold so many bonds even now and despite the negatively sloped curve is interesting – the Fed is clearly not a profit-maximizing institution, but others are probably there simply to avoid having to mark-to-market their holdings.

Another important source of funding for the Treasury market has of course been the foreign sector. Despite rumours to the contrary, foreign central banks do still own US bonds and there have also been substantial private sector flows over the last 15 years.

In fact, it is our belief that many of the foreign flows over the last 20 years have been the result of either overt QE-like policies in the investors’ home countries (the Bank of Japan’s Mr Kuroda clearly hoped to weaken the JPY by using domestic QE to force Japanese institutions to invest overseas, while M. Draghi certainly set out to achieve something similar with the QE/EUR), or the flows may have been by-products of domestic credit booms in countries such as China.

We now know that China’s private sector has exported at least $2.5 trillion since the year 2000, although in reality the true number maybe somewhat higher. Of course, not much of this money will have gone directly into Treasuries or other G7 government bonds, but it is a fair bet to assume that at least some of the settlement received by US and other property vendors who sold to PRC entities will have ultimately placed funds into the bond markets. Credit booms in far-flung places abroad have created a demand for OECD bonds.

There is also the “vendor financing” aspect of US bond purchases by Emerging Markets. The last 20 years has witnessed a marked increase not just in US imports from EM but also US investor flows into the EM. Both of these flows implicitly place upward pressure on the EM currencies and therefore oblige the EM central banks to intervene by buying USD assets, principally Treasuries, if they wish to defend their exchange rates – as many still do. In theory, a US mutual fund investor buying EM equities with the proceeds of a previous US QE injection ends up forcing an EM central bank to buy yet more Treasuries “on top of” the Fed’s original purchases.

It would be our contention that the persistent use of QE by developed world central banks; the leakages from China’s unprecedented domestic credit boom; credit booms elsewhere, the structure of Western markets vis-à-vis leverage collateral and nature of Mark-to-market rules; and the “vendor financing model in EM” have created a very biased market in bonds that has freed real money savers and investors of the need to fund what could be assumed as being extreme government deficits over the last 15-20 years. Hence, real yields have generally remained low despite extraordinary levels of government borrowing that in times gone passed would have been assumed to have been inflationary in themselves.

Given the Treasury markets’ pre-eminent role in global finance, this wall of “funny money” (essentially credit financed at its core) into the bond markets has then infected and circulated around other financial markets, thereby creating the liquidity & narrative-driven markets that we are suffering – markets that are beset by “free surface effect” sloshes of liquidity from one side to the other…

However, now that QE seems to have ended and China’s credit boom has indeed finally ended, global capital flows will most likely weaken and the various “funny money flows” into bonds have either stopped or gone into reverse at a time during which budget deficits are being inflated by increased defence spending. The scene is being set for a nasty rise in real yields and a consequent liquidity crunch.

The Post 2009 system is, therefore, becoming increasingly vulnerable to a government funding crises (-a series of UK/Truss like moments…) and we are seeing this play out in yields even as we write.

As the crises loom, some governments will undoubtedly blink. Arguably, most governments have become too used to soft budget constraints and too indebted to do anything else. In Japan, we have little doubt that the MoF will force the BoJ back into a quasi-QE stance – perhaps calling it a PKO rather than YCC but the intention will be clear. The ECB’s “whatever it takes mantra” will likely force it back into the markets. Indeed, the ECB has already been quietly buying bonds when needed over the last six months. These central banks would rather suffer stagflation than depression – Japan’s government might even welcome inflation.

In the USA, it has been our assumption that Yellen-Powell will soon seek to restrain yields by running down the government’s rather substantial stock of deposits (essentially a form of QE) and suspending QT. We had expected the deposit drawdown to occur against the background of monthly budget deficits in May, June, and July but now we find ourselves wondering if the authorities will use the cash to retire bonds over the coming weeks, and in so doing attempt to directly support the debt markets sooner rather than later.

Of course, all of this is conjecture and forecasting. Japan – or even Europe – may drop the ball and perhaps the stubborn (if largely historical) inflation data will thwart any plans that the US may have to manipulate bond markets. Yields could continue rising through the middle of the year if the authorities do not act, although we think that they will act. Certainly, it will be imperative to continuing watching the short term monetary and financing data (rather than just listening to all the noise in the media about short term rates) for any signs or clues to tell us whether policy is easing or tightening as the roller coaster ride in bonds continues.

Disclaimer: These views are given without responsibility on the part of the author. This communication is being made and distributed by Nikko Asset Management New Zealand Limited (Company No. 606057, FSP No. FSP22562), the investment manager of the Nikko AM NZ Investment Scheme, the Nikko AM NZ Wholesale Investment Scheme and the Nikko AM KiwiSaver Scheme. This material has been prepared without taking into account a potential investor’s objectives, financial situation or needs and is not intended to constitute financial advice and must not be relied on as such. Past performance is not a guarantee of future performance. While we believe the information contained in this presentation is correct at the date of presentation, no warranty of accuracy or reliability is given, and no responsibility is accepted for errors or omissions including where provided by a third party. This is not intended to be an offer for full details on the fund, please refer to our Product Disclosure Statement on nikkoam.co.nz.