Major “events” in markets have been caused by wrong assumptions over mathematical relationships. The Long Term Capital Management Debacle (LTCMD) in 1998 was primarily the result of the incorrect assumption of perfect markets by a cluster of Nobel Laureates. The naïve and wrong assumptions over correlations proved to be the spectacular undoing of the mortgage markets in 2007-8. In both cases, investors had explicitly put their faith in the notion that markets were perfect, and that the system was made up of thousands of uncorrelated independent actors with perfect knowledge and rational expectations. These assumptions were made despite the clear evidence to the contrary; expectations are often adaptive and trend following and that the financial industry is dominated by a relatively small number of behemoths.

Central banks have of course always played a role in markets and setting expectations but, since the mid-1990s and in particular since the GFC, they have not only become ever more indirectly involved (one might ask whether the rise of the central bank “put” / moral hazard issue explains why households now run with higher levels of risk in their financial portfolios) but they have become directly involved in setting yield curves. The Federl Reserve and US Treasury’s direct manipulation of the yield curve over recent years implies that there is now a large non-profit-maximizing entity dominating what is in reality the nearest thing that we have to a numeraire within the global financial system (i.e. the UST market).

Indeed, it would be difficult to think of a situation that is further removed from the conditions required by the Perfect Market Hypothesis. This, of course, implies that much of what is taught with regard to conventional portfolio analysis and theory is compromised. If the numeraire or base of the system is compromised, then any valuation tool based upon it must also be inherently suspect. We might even go so far as to suggest that valuations “don’t matter” in this world.

During my academic days, General Equilibrium Theory seemed an interesting topic, but it was unfortunately taught badly. However, one thing that did stand out from Professor B’s chaotic lectures was that if one market was in a disequilibrium because or some form of interference or failure, then so too would many others – if not all markets.

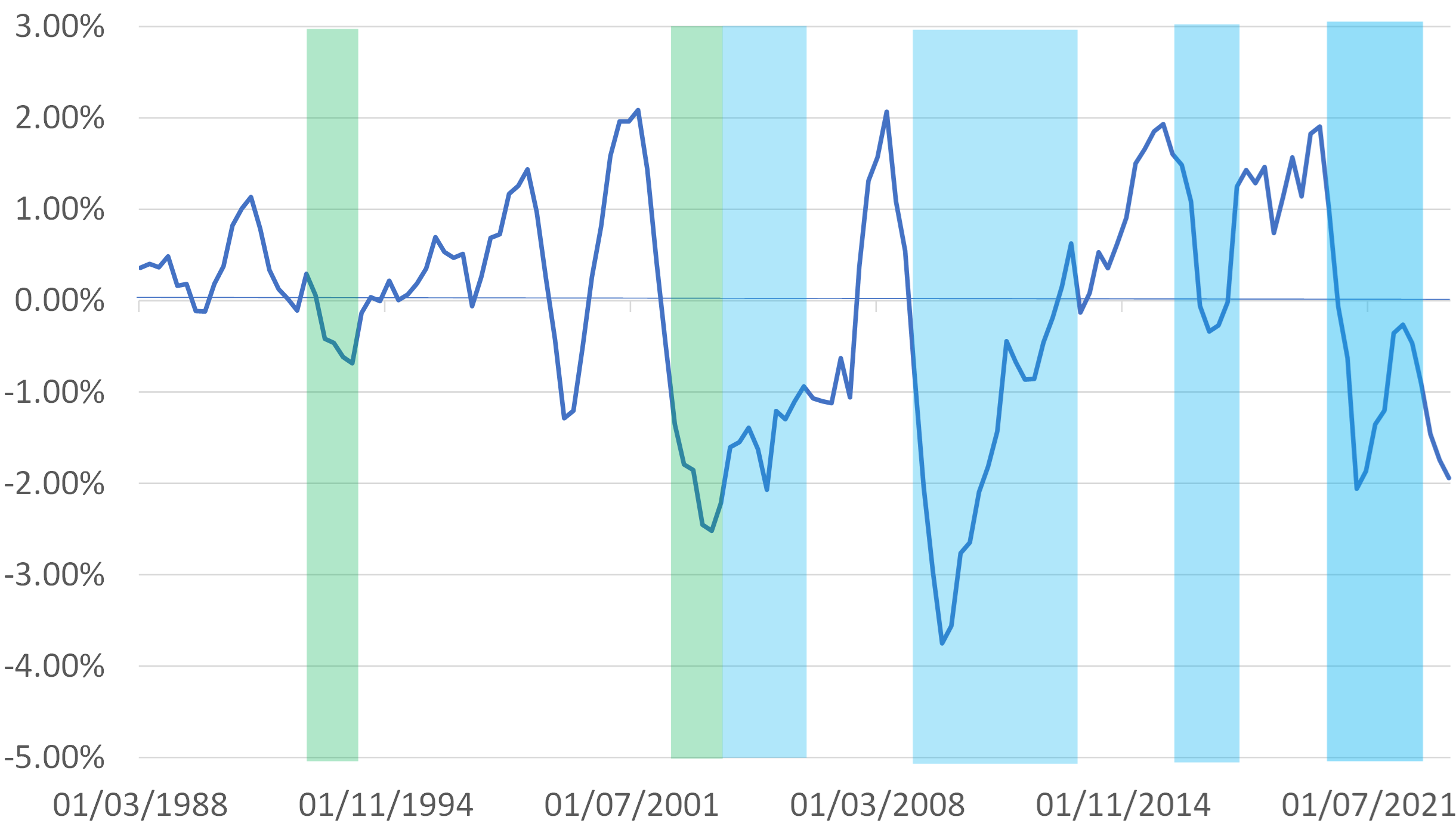

Quantitative Easing and the practical realities of governments that wish to run large “Greater Public Deficits” have as implied that central banks have created a false market in savings. Quite simply, because governments in much of the developed world have wanted to borrow substantially more than their households (and companies) save, the central banks had to intervene by creating “funny money financing” through QE and quasi-QE (i.e. YCC) policies. Modern Monetary Theory, or the Magic Money Tree have a lot to answer for but without them governments would have run into multiple financing crises since the early 1990s. The shaded areas in the chart show when we have witnessed either de facto QE (green) or explicit QE (blue).

G7: Household Net Saving Minus Government Net Borrowing % GDP

The authorities have therefore interfered with the most important market within the financial system and thereby sustained a disequilibrium / lack of genuine price discovery at the centre of the system. This has then in turn affected other markets across not just the financial system but also the real economy. Below, we list some of the most egregious examples.

Low yields in sovereign bonds have obliged yield hungry investors to move out the risk curve. Particularly in the EZ, we have noted how the realized returns to savers have lagged the cumulative sum of household savings. For example, the increase in the net value of German net foreign assets over the last 20 or so years is less than their historical cost (as modelled by the country’s cumulative current account surpluses). The situation in worse in Switzerland, less poor in France and Italy, but in general realized returns have been poor due to the succession of “blow ups” that investors have suffered as they have been obliged to chase returns in the wrong markets.

Ultra-low yields have encouraged house prices to rise to extraordinary levels relative to the general price level and of course wages. Speculation and leverage have clearly played a role here, the high level of prices is not simply the result of household growth. High house prices do however impose a cost on the economy and of course on the cost of doing business in the locale – both directly and via their impact on the “subsistence wage”.

Just as most countries that we visit talk about a Housing Affordability Crisis, most also talk about a labour shortage. It is not just the US JOLTS data or Japan’s Job Offers to Applicants Ratios that are elevated. It is possible that the (Pandemic-era) fiscal largesse allowed by QE has lowered the incentive to work but we also wonder whether high accommodation costs imply that would-be workers cannot afford to move to the areas in which they are required, unless wages rise to levels that the companies cannot afford to pay given their own (property) costs and revenues. This creates a perverse Word of supply-constrained output and employment that can only be solved via a burst of wage and price inflation relative to property prices.

The miss-allocation of capital. This is a well-known feature of easy money and low yields and we have seen it manifested in sparsely occupied tall buildings (modern day cathedrals) across the World for decades. However, how many “disrupter companies” that never made a profit themselves, but which sabotaged the profits of incumbent companies, were able to exist purely because “money was cheap”?

Excessive and destabilizing global capital flows. History is littered with examples of Emerging Markets (and others) receiving such large inflows of capital when Western monetary conditions are easy that they not only fritter away the money on unwise flagship projects, but also become addicted to capital inflows and overly indebted. Asia in the run up to the 1997 crisis represents a clear example, but there have been many more recent examples…. EM Debt Crises are usually the outcome of such cycles.

Inflation. Ultimately, the central banks’ aim was to support Aggregate Demand and if supply is not forthcoming, this will be inflationary. In places in which supply has been forthcoming – chiefly in the goods markets as a result of North Asia’s tendency to maximize output rather than profits (another important source of distortion / disequilibrium within the global system) – price inflation has not occurred, but we have of course witnessed a great deal of inflation in domestic services over the last 30 years. Inflation distorts genuine price signals and also undermined efficiency and productivity.

This list is by no means complete but clearly it touches on the most important sectors of the economy – savings, accommodation, international trade, financial stability, price stability and of course long-term growth potential. The central banks’ activities that have interfered with bond markets may have given rise to elevated asset prices and to enlarged financial sectors, but they have done material harm to the real economies and therefore to the welfare of the “median citizen”.

We cannot help but feel that it has been this failing that has created the rather fraught political environment in which we find ourselves. QE has aided wealth and income inequality, and this has been perhaps its biggest legacy – one that will be felt in election across the globe over the next few years.

The second implication is that Global Supply Side growth will remain constrained. AI may well lift productivity in specific areas and profits will be made either supplying its infrastructure or using it, but as the late 1990s tech boom showed, this does not necessarily imply that overall productivity across the whole economy will rise. In a sense, the equity markets already know this, judging by the recent concentration of returns.

If I have an “economics faith”, it is that the market system will try to find its way back to an equilibrium position. This will be hard whilst governments remain so engaged in our economic systems, but this has only been made possible by the central banks’ provision of “funny money funding”. We would argue that if we take away the funding, then the distorted world that has created disequilibria will be unsustainable and the system will be able to move towards something more sustainable and efficient.

Ultimately, the solution to the dis-equilibria could be as simple as allowing price discovery within the sovereign bond markets. But, we are only too aware that if bond yields were to spike – as they threatened to do last October – then a great number of things will break. Some governments would become insolvent - particularly with the confines of Fixed Exchange Rate regimes. If the decline in bond prices were to be rapid then long-term savings institutions would suffer immediate stress (as in the Truss Moment in Gilts). Problems within the commercial real estate sector would be crystallized and the private markets would likely wilt. Financial institutions might fail. House prices would deflate – following Japan’s example from the 1990s - and negative equity would create a doom-loop as recessions unfolded.

Quite simply, the central banks cannot, today, simply walk away from the World that they created unless they are prepared for (very) bad things to happen. But, one day, they will have to walk away.

A better outcome would be a voluntary deregulation programme by governments and a boom in productivity that allows real wages to rise. This would involve not just luck but a massive re-thinking of the business environment and the way we spend money. How does one raise productivity in the service sector while maintaining a level of service sufficient to attract customers? As the BoJ admits, one of the biggest impediments to raising productivity in Japan’s service sector over the last thirty years has been the nature of services that customers want. We would argue that one can hope for a productivity renaissance to solve the world’s problems, but one should not expect or rely on such an outcome.

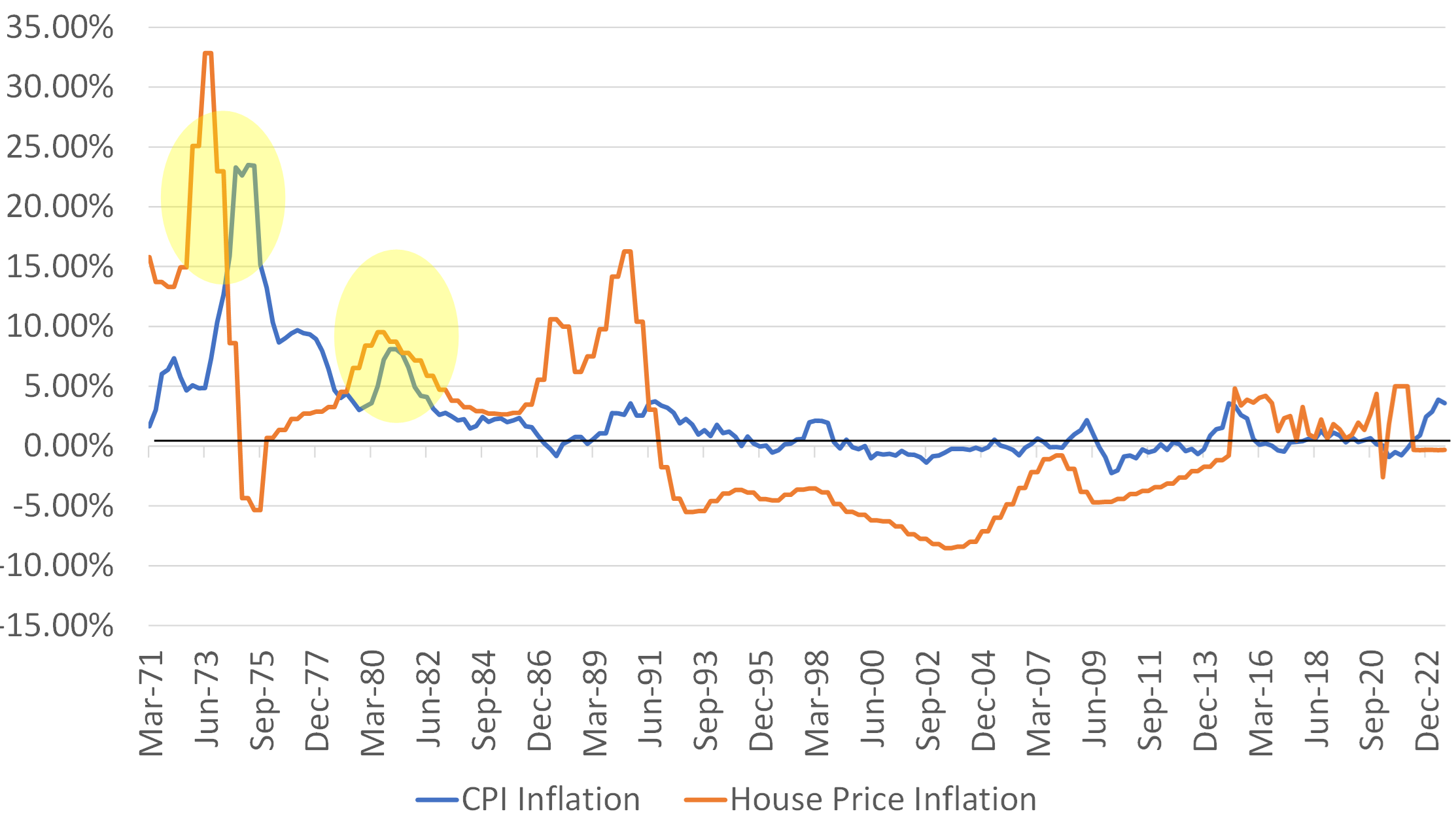

For us, the only viable solution is general inflation. Central banks should endeavour to keep rates high enough and monetary conditions tight enough to constrain the highly leveraged sectors of the economy, such as housing, but not tight enough to prevent wage and price inflation. Just as we did during the mid-1970s and early-1980s, we need higher inflation to deflate the real value of the debt that has been created this cycle and to bring down real asset prices to more equilibrium-like levels. Once this is achieved, central banks could then move to control inflation through conventional means, just as they did during the early- mid 1980s. However, we must emphasize that before we have the 1980s, we must first have the 1970s – tightening too soon would give us the 1930s or even Japan’s 1990s.

Japan: CPI and House Price Inflation % over 12 months

It may seem ironic or even perverse that we are advocating more inflation as a “cure” given that it is something that we have listed as being a “negative consequence” above, but it would be very much the lesser of the two evils that are on offer, and central banks know how to deal with inflation over the longer term; deflation is a tougher nut to crack…

It is with this in mind that we believe that the coming months will be crucial. With so many of the World’s populations going to the polls this year, we can assume that many governments will be endeavouring to support growth through yet more fiscal spending and probably funny money financing. If they do this – which seems likely – then we would urge investors to seek “inflation protection” in markets – by being a little short duration in fixed income and to look for companies with pricing power in their equity portfolios. Finally, looking for “Hard Currencies” that will protect the real value of their money on a sustained basis may lso be a worthwhile endeavour. The next few months will likely decide the inflation / deflation debate and investors will need to react accordingly.

Disclaimer: These views are given without responsibility on the part of the author. This communication is being made and distributed by Nikko Asset Management New Zealand Limited (Company No. 606057, FSP No. FSP22562), the investment manager of the Nikko AM NZ Investment Scheme, the Nikko AM NZ Wholesale Investment Scheme and the Nikko AM KiwiSaver Scheme. This material has been prepared without taking into account a potential investor’s objectives, financial situation or needs and is not intended to constitute financial advice and must not be relied on as such. Past performance is not a guarantee of future performance. While we believe the information contained in this presentation is correct at the date of presentation, no warranty of accuracy or reliability is given, and no responsibility is accepted for errors or omissions including where provided by a third party. This is not intended to be an offer for full details on the fund, please refer to our Product Disclosure Statement on nikkoam.co.nz.