BOJ’s latest YCC tweak underlines central bank focus on wage developments

On 31 October the Bank of Japan (BOJ) announced that it would allow the 10-year Japanese government bond yield to rise above 1% under its yield curve control (YCC) scheme. The timing of the BOJ’s latest YCC tweak, which nudges the central bank another step towards monetary policy normalisation, may have surprised some. After all, the YCC tweak was the BOJ’s second in three months; the central bank had just raised the YCC ceiling to 1% from 0.5% in July.

That said, the BOJ’s decision to again lift the YCC ceiling is not surprising when we bring Japan’s wage trends into the picture. Whether the rise in wages witnessed recently in Japan can be sustained over the longer term and eventually outpace inflation is seen as a key consideration for the BOJ as it plots a way out of quantitative easing. It is no secret that wage growth is one of the several developments BOJ Governor Kazuo Ueda is focusing on, and he appears to be keeping a particularly close eye on the target percentage pay increase component, known as “base-up”, that labour unions negotiate with employers. Just prior to the BOJ’s monetary policy meeting in October, Rengo, Japan’s biggest labour union, decided to demand a base-pay hike of 3% or more at the annual wage negotiations scheduled in the spring of 2024. Rengo has firmed up its demand after asking for “around 3%” a year ago.

Rengo’s confidence may have prompted the BOJ to act a littler earlier than it intended; if the union’s base-up demand is met following negotiations next spring, that would affect a significant number of full-time workers and help pave the way for the sustained rise in wages that the central bank is looking for. The BOJ will likely need further signs—winter 2023 bonus payments may be one—before it acts more decisively. However, Rengo’s confident stance probably gave the BOJ an incentive to stay ahead of the curve as it could lead to a secular, rather than a cyclical, rise in wages by impacting a significant portion of the overall work force.

One thing to keep in mind is that the BOJ’s policy decisions should not be viewed through the lens of a weak yen. At a time when interest rate gaps between Japan and those of other developed economies have widened to historical levels, some commentators often portray the steadily depreciating Japanese currency as an incentive for the central bank to adjust its easy policy. While the yen is no doubt a concern for the BOJ, it may be worth remembering that halting the currency’s depreciation through official means falls under the purview of the government.

Japan’s demographics may be getting positive views, but it’s really about labour

Until recently, Japan was a prime example of a developed but stagnating economy, often described as a country in slow decline. One of the negatives attributed to Japan was its demographics, with the population shrinking and ageing due to a low birth rate. However, now that the country is shaking off deflation and seemingly on the cusp of a resurgence after decades spent in the doldrums, some foreign media outlets have seemingly begun to view Japan’s demographics positively. For example, the relatively old society—the government announced in September that more than 10% of Japan’s population is aged 80 or older—has been described as a model of efficient wealth distribution. A more intriguing view mentioned recently is that Japan’s demographics favour the economy as it tightens the labour pool at a time when demand for workers is increasing, which in turn could help corporate Japan become more efficient.

Japan’s demographic makeup may indeed be a factor tightening the supply of labour, but this is not a new phenomenon as Japanese society has been ageing over the course of several decades. The labour shortage Japan is currently experiencing is due to more recent developments. An increase in demand for Japanese goods (especially from the US, which was then emerging from the pandemic) in turn boosted domestic exporters’ demand for labour. And when economic activity returned in earnest after the pandemic with the country re-opening its doors to foreign visitors, Japan began experiencing an acute shortage of workers amid a recovery in domestic demand.

The acute shortage of workers could be a golden opportunity for Japan Inc. to become structurally efficient with the least amount of pain. Increasing competition for limited labour equates to higher wages for workers, and perhaps more importantly, a much more liquid labour market. Higher labour market liquidity means that Japan can potentially see its work force become much more mobile and flexible, streamlining corporate efforts to attract the best and the brightest with job-hopping becoming even less of a taboo. Before the labour shortage, Japan would have had to introduce painful measures, such as allowing companies to enable mass layoffs, if it wanted to initiate once-in-a-generation structural reforms. However, the current labour shortage allows market forces to initiate such changes naturally, which is significantly positive from a market and economic perspective.

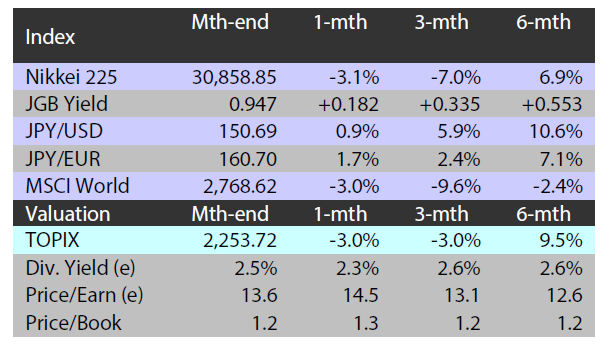

Market: Japan stocks slip in October amid a rise in US long-term rates

The Japanese equity market ended October lower with the TOPIX (w/dividends) down 2.99% on-month and the Nikkei 225 (w/dividends) falling 3.13%. Based on US Federal Reserve officials’ cautious tone on rate hikes, initially concerns receded regarding a prolongation of US monetary tightening, which acted as a tailwind for Japanese stocks. However, the market declined overall due to a combination of negative factors including Japanese and global equities appearing relatively richly valued as a result of the rise in US long-term interest rates, an outlook for a continuation of US monetary tightening taking hold again on the back of the country’s release of strong macroeconomic indicators, and the intensification of the conflict in the Middle East leading to stronger risk-off sentiment in the market.

Of the 33 Tokyo Stock Exchange sectors, 4 sectors rose, with Foods, Pulp & Paper, and Banks posting the strongest gains. In contrast, 29 sectors declined, including Pharmaceuticals, Machinery, and Iron & Steel.

Exhibit 1: Major indices

Source: Bloomberg, as at 31 October 2023

Source: Bloomberg, as at 31 October 2023

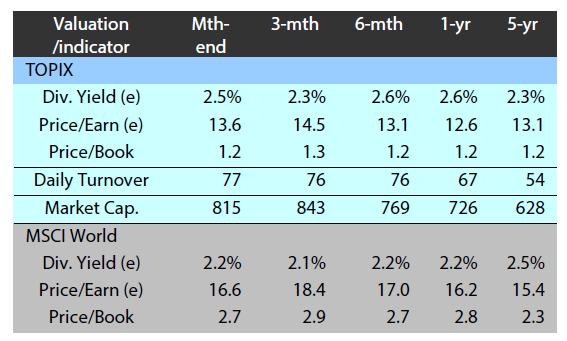

Exhibit 2: Valuation and indicators

Source: Bloomberg, 31 October 2023

Source: Bloomberg, 31 October 2023