One cannot turn on a financial news programme at present without hearing some talking-head or other discussing the outlook for interest rates, almost as though they are the only thing that matters to markets or the economy. We suspect that the matter to a degree to the latter, and much less to the former than is generally accepted.

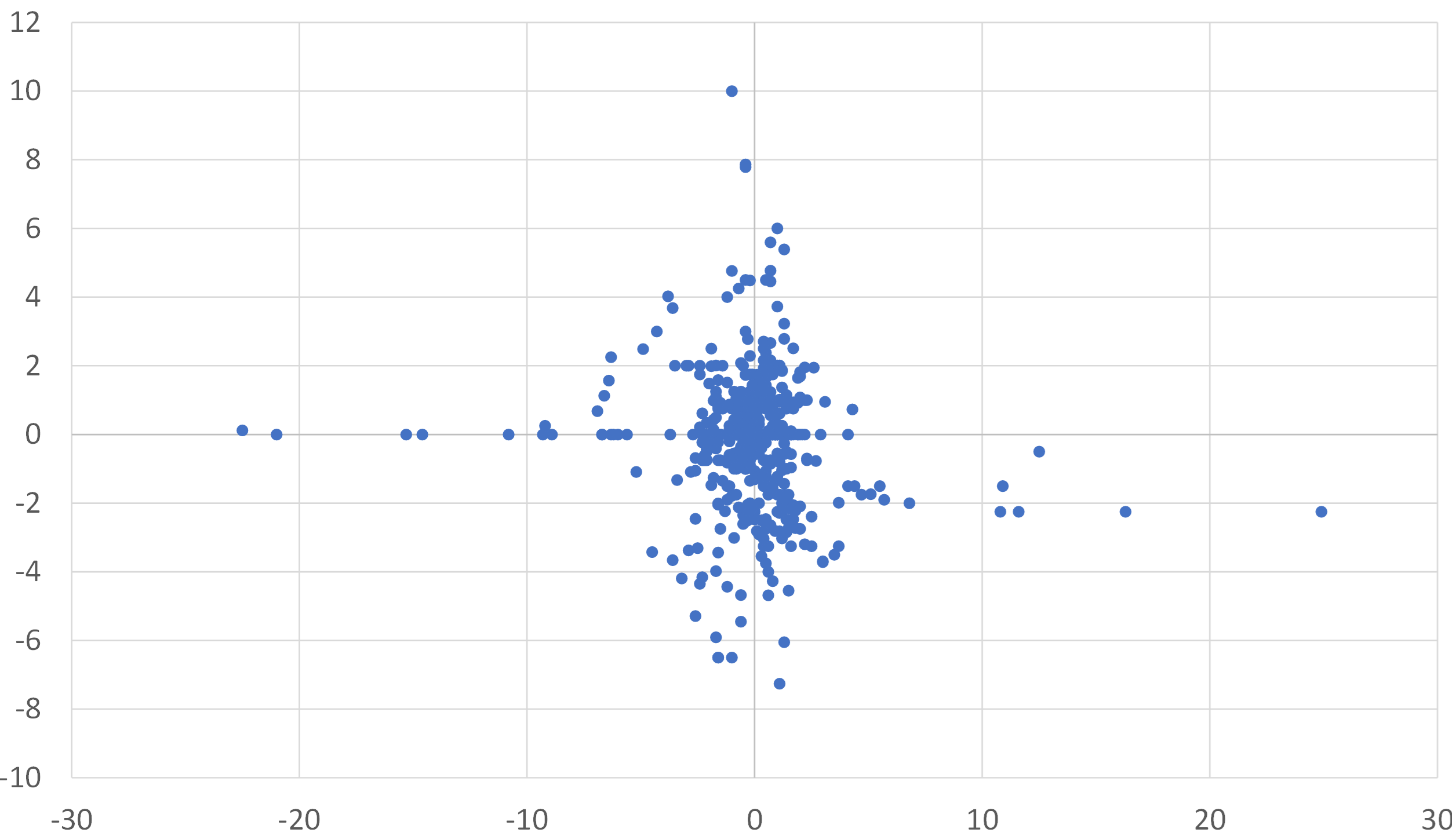

The textbooks (rightly) suggest that interest rates are the reward for delaying consumption – higher rates should make people save more but unfortunately the evidence for this working in practice is scant. Ultimately, it is the real interest rate that matters in such a time preference model, but each person has a different price index, different inflation expectations and, most likely, a different view of their own likely income life cycle. Hence, the actual impact of changing interest rates on people’s savings behaviour is at best unpredictable and at worst hard to identify. It would be a brave analyst that suggested that they could decipher a relationship within the chart below.

USA: Change in Savings Rate vs Change in Fed Funds 1980 - 2023

Of course, if you are a mortgagee that is over-exposed to a deflating property market, rising rates may feel uncomfortable (i.e. the real rate of interest may feel quite high) and this may encourage you to spend less, save more, and maybe even retire some debt. However, if the mortgagee is over-extended and also suffering weak income growth or even unemployment, then the situation may be dire, and bankruptcy could be a real possibility. This is why we only worry about negative wealth effects when they are accompanied by weak income trends and / or rising unemployment.

Moreover, inasmuch as a country cannot be indebted to itself, the chances are that the majority of debt in an economy is “owned” by domestic savers who should be receiving a benefit to their incomes from rising rates. Certainly, higher rates should have both costs and benefits to any economy.

In general, it is probably fair to suggest that rising yields detract from the effective disposable incomes of borrowers and add a little to the incomes of savers, while (notwithstanding our earlier comments) do tend to dissuade real people from borrowing and perhaps even encourages them to save a little more. On balance, the desire to borrow in order to advance consumption will be lessened, and the desire to save will be increased, thereby lessening the demand for credit from the real economy as rates increase (i.e. the demand curve is conventionally shaped, even if the coefficients are uncertain and in all probability unstable).

Meanwhile, the global banking system is clearly less inclined to lend than it was two years ago. The US banks have significant funding concerns following the gyrations in the deposit markets that have occurred since 2020, and the Euro Zone banks have seen their funding from the ECB cut back materially. Add to these factors some pressing concerns over geopolitics, the potential for increased FX volatility, rising loan losses (particularly as lending rates rise) and capital adequacy issues, and we can suggest that the supply of credit to real world borrowers is tending to contract at present. This is certainly the case within the USA, Europe, Asia and Australasia at present.

With income trends somewhat subdued in the USA, and simply weak almost everywhere else, the softness in credit supply and its higher cost clearly lowers people ability to spend, unless of course they have savings available that they are prepared to “dip into”. In Europe, households probably have already exhausted their stock of pandemic-era excess savings, while in the USA households have we estimate another three months’ worth to spend, while in Japan and the UK there may still be a year to go before savings are rundown.

This difficult – to quantify - savings overhang creates a problem for the central banks, in that the household sector’s response to higher rates and tighter credit supply will take longer than usual to come through because of the Post Pandemic savings situation. However, when the savings are finally exhausted, consumer expenditure trends could easily face a Wile E Coyote moment. Arguably, this is already unfolding within the EZ.

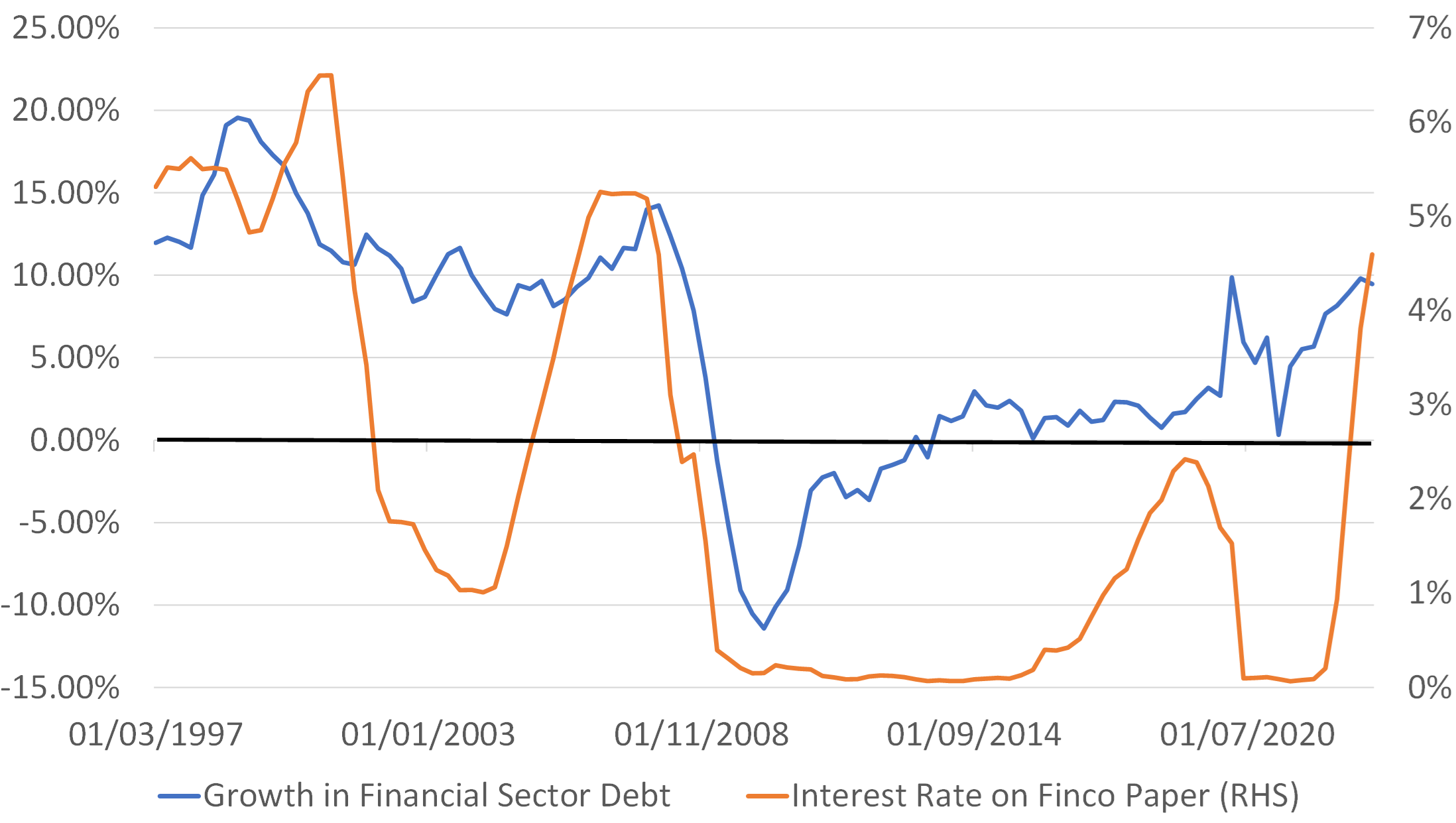

However, credit is not only used by “real people” and mainstream commercial companies. Much of the credit growth within the economy occurs inside financial sector itself, as banks borrow from each other, lend to other suppliers of credit, and of course provide leverage to investors in many markets. As the chart below shows, trends within this type of credit seems to pay little heed to what interest rates are doing at any given time – sometimes the credit data leads the interest rate data, sometimes the reverse is true and sometimes there simply is no relationship between the two series.

USA: Grwth in Financial Sector Debt % YoY; % p.a

Currently, financial sector credit is booming even as the Fed raises rates and we suspect that if we could properly update this chart to this month, it would show a further acceleration in credit growth within the sector.

At present, banks may not wish to lend to real world entities or even against property as collateral, but they are very keen to provide short term “repo-like” credit to those funds that have the necessary collateral (usually T bonds). The banks see this activity as low risk, easy to unwind if they suffer funding issues themselves, and although the margin may be slim, the quantities involved can make this a profitable endeavour for them. Of course, higher rates make the lending more not less attractive.

Moreover, the current and ongoing shrinkage in the Fed’s Reverse Repo scheme (caused by heavy T Bill issuance and savers moving out of Money Market Funds in favour of risk assets) is providing the major investment bank with fuel for this type of lending. Banks may not be able to use the funds that are now residing in their clients’ broker accounts to make long term mortgages, but it is the perfect fuel for proving repo loans to both domestic and (more surprisingly) foreign borrowers.

This latest intra-system credit boom has clearly lifted risk asset prices, helped to provide a bid for T bonds, and weakened the dollar’s external value. Inasmuch as the Federal Reserve’s preferred “gauge” for the assumed stringency of its policy mix is based around a Financial Conditions Index, which includes equity prices, credit spreads and other prices, the renewed asset price inflation that the intra financial system credit boom is causing is leading to the Fed’s FCI suggesting that the central bank may in fact be too loose and telling it that it needs to tighten further. Hence, it intends to do more QT (which will make the credit crunch in the real economy worse) and potentially raise the Fed Funds rate further.

Once again, we may think that with money and credit growth collapsing, the credit crunch worsening, and demand pressure falling, the Fed could afford to stop tightening, but this is not what the central bank’s own models will be saying to them.

We certainly feel, on the basis of our forecasts, that the Fed risks overtightening if it continues along its current advertised path, but we are not sitting in Washington, we are not subject to political forces, and we would like to think that we would not take much notice of the message provided by the FCI. We have never been fans of the latter and are conscious that they have laid behind a great many policy errors, including as recently as 2021.

It is not only policymakers that face a difficult time; so too do investors. In the very near term, the continuing boom in intra financial system credit makes us bullish asset prices and bearish the US dollar. But, looking ahead, we can expect the US Treasury to start issuing bonds towards the end of the third quarter, just as the economic slowdown starts to come into focus. Yields may therefore rise a little even as growth slows and, if this causes investors to swap risk assets for money market funds again, then the fuel for the recent reflexive / procyclical intra-system credit boom will be removed and asset prices could then reverse their recent “melt up” even as interest rate expectations moderate. However, if the credit boom does end later this year and financial asset prices begin to weaken as the real economy falls into recession and (CPI) inflation falls away, then the Fed’s FCI will argue for an easing markets will then be able to look forward to a shift to an easier stance in 2024 (perhaps even more QE, albeit via a different “funding for lending” route), an expectation that could start the whole leverage boom process off again.

We would argue, as Keynes did a century ago during similar circumstances, that this intense instability and volatility in monetary conditions and even growth is “no way to run an economy”, and even a recipe for low productivity growth / stagflation over the medium term, but this apparently is the price that we must pay for our overly financialized economies and systems.

Disclaimer: These views are given without responsibility on the part of the author. This communication is being made and distributed by Nikko Asset Management New Zealand Limited (Company No. 606057, FSP No. FSP22562), the investment manager of the Nikko AM NZ Investment Scheme, the Nikko AM NZ Wholesale Investment Scheme and the Nikko AM KiwiSaver Scheme. This material has been prepared without taking into account a potential investor’s objectives, financial situation or needs and is not intended to constitute financial advice and must not be relied on as such. Past performance is not a guarantee of future performance. While we believe the information contained in this presentation is correct at the date of presentation, no warranty of accuracy or reliability is given, and no responsibility is accepted for errors or omissions including where provided by a third party. This is not intended to be an offer for full details on the fund, please refer to our Product Disclosure Statement on nikkoam.co.nz.