The media is abuzz with stories about the demise of the US Dollar as a reserve currency and the rise of alternatives, such as the proposed new “BRICs” currency. From our perspective, we cannot think of a worse monetary idea than a pan-BRIC currency. It is difficult to conceive a less optimal currency area i.e. one worse than the Euro Area, which has certainly had (and continues to have) its problems.

If the project does come to fruition, we suspect that it will fail with the first symmetric terms of trade shock. For example, falling commodity prices would aid South Africa and Brazil but disadvantage India and China, creating immense centrifugal forces. It seems to us that the one thing that those countries that are calling for the end of the dollar have in common is not their economic cycles, but the fact that they are countries that don’t have any dollars…

Contrary to popular opinion, this group now unfortunately includes much of Asia once again. History has shown that the Asian economies traditionally run on two distinct fuel types:

- 1. Export growth

- 2. Credit

For both of these factors, the supply of US dollars is still of vital importance; most of Asia’s exports continue to be priced in dollars, and shipment volumes are still very sensitive to the trajectory of US spending. Meanwhile, the Asian currencies’ longstanding links to the US dollar (both formally and informal) imply that domestic US monetary trends are reflected in local conditions - something which – often happens in an amplified form. Seemingly, this would explain why when the US catches a cold, Asia often contracts something worse.

Looking at things from another angle, although there may still be some residual strength in the US consumers’ demand for services, it is becoming increasingly apparent (and maybe obvious to some) that households in the US, and around the world, are now satiated with goods. Indeed, if one excludes the effects of inflation on the sales data, one can see that in much of the OECD, the demand for goods is contracting.

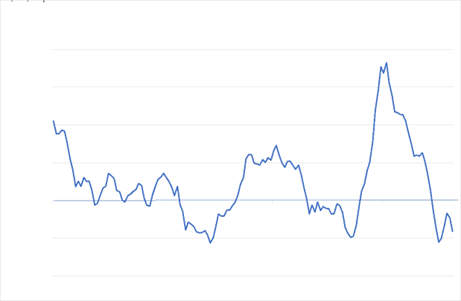

For Asia, this has translated into weak export revenues (particularly in dollar terms), an extreme accumulation of inventories, and – of course – deep cuts in production. Indeed, the data is beginning to look just as disturbing as it did immediately following the Global Financial Crisis and even the more recent Pandemic. It is also apparent that, faced with the chronic accumulation of inventories, some companies are resorting to heavy price discounting; export price deflation is back in Asia, which has been a key component in the slowdown of inflation rates in the West. Usually, falling export prices in Asia represent good news for global bond markets, but this also comes at the expense of depressed profits in the corporate sector.

To make matters worse, higher-than-usual US interest rates and reduced cross-border credit flows have dealt a blow to Asia’s banking system. Not only do Asia’s central banks tend to shadow the Federal Reserve when it comes to their own interest rate-setting behaviour, but many of the individual banking systems – including that of China - actively utilise dollar borrowings to finance their own lending activities.

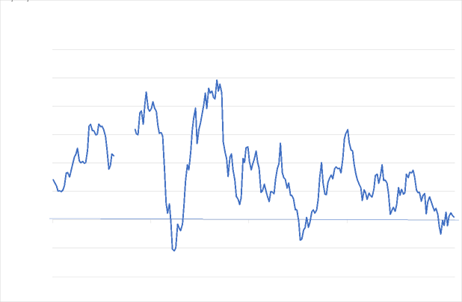

While data is often murky, it is gleamingly clear that much of the funding for Asian credit growth has come from the global dollar-denominated credit markets over the last six to seven years. With US interest rates close to zero but local rates much higher, there was an obvious incentive for banks to fund offshore and hope that the interest differential exceeded any currency risk. Of course, this simple arbitrage has left many of Asia’s financial systems with substantial dollar-denominated foreign debts on their balance sheets.

Unfortunately, the Fed’s recent tightening of US conditions has impacted both the ability of new dollar funding and the servicing cost of the older debt, much of which is relatively short-term. Old hands will, of course, recognise this narrative from the mid-1990s, when Asia’s banks had previously made heavy use of dollar funding in the pursuit of easy margins. Indeed, rather chillingly, Asia’s most recent credit data is beginning to look quite similar to that experienced during the banking crisis years of 1997/8.

This weakness in the credit data has already been reflected in the local property markets, in which prices have been soft and transaction volumes depressed. In time, these trends will also be reflected in weaker domestic demand trends. In the case of China, this has already been the case.

Optimists will no doubt argue that to resolve the problem of weak domestic credit, all that needs to happen is a reduction in interest rates. While this is an answer, it is not the solution. Cutting rates will likely cause (much) weaker currencies and, therefore, a further rise in the servicing costs of the foreign debt that has been incurred. The Thai central bank attempted this route in June 1997, and the results were far from positive.

In fact, if the Asian region is to regain any room for manoeuvre in regard to its domestic policy settings, it first needs to repay its external debts. For this to happen it needs dollars, but the only way in which these dollars can be earned is via trade, which, as we mentioned above, is currently also very weak.

Asia is, therefore, facing a perfect storm of weak export and sales revenue trends and weak domestic credit trends that are undermining its property markets and perhaps even financial infrastructure. The currency and equity markets have already started to discount this, although we fear there is more weakness to come.

Of course, weakness in China and the rest of Asia represents a notable drag on global growth. We estimate that Asia’s debt repayment problem will represent a 2% global GDP headwind to the World economy. The most obviously affected countries will be those that export to China. Germany, Australasia and many of the world’s commodity producers are also being affected, but so are those that import from the Region. These countries will be transferring their incomes to Asia when they pay for their imports, but the Asian financial systems will then implicitly ‘consume’ this money by using it to repay debt rather than re-investing it back into the global system. What was Asia’s problem will eventually touch us all.

In the long term, the 2023 experience argues that Asia urgently needs to stop talking about decoupling and seek to make this a reality by moving away from relying on the US dollar as a monetary anchor in favour of their own domestic currencies. However, simply moving from a USD obsession to an RMB or even BRICs target will not solve the problem; it will merely shift its centre and focus.

It would be much better for each country to utilise their own national credibility and “go their own way” into a world of freely floating currencies. This shift would also allow countries to finally consider types of long-term structural reforms that they can use to move away from their export dependency and towards more economic self-determination. More controversially, but as Singapore showed twenty or so years ago, this type of transformation often involves a political dimension, something that some governments may not yet wish to face.

Disclaimer: These views are given without responsibility on the part of the author. This communication is being made and distributed by Nikko Asset Management New Zealand Limited (Company No. 606057, FSP No. FSP22562), the investment manager of the Nikko AM NZ Investment Scheme, the Nikko AM NZ Wholesale Investment Scheme and the Nikko AM KiwiSaver Scheme. This material has been prepared without taking into account a potential investor’s objectives, financial situation or needs and is not intended to constitute financial advice and must not be relied on as such. Past performance is not a guarantee of future performance. While we believe the information contained in this presentation is correct at the date of presentation, no warranty of accuracy or reliability is given, and no responsibility is accepted for errors or omissions including where provided by a third party. This is not intended to be an offer for full details on the fund, please refer to our Product Disclosure Statement on nikkoam.co.nz.