We suspect that many investors have become accustomed to a seemingly synchronized world with relatively little currency volatility – in a sense over recent years we seem almost to have been back in the 1960s, a period during which moves in exchange rates were quite rare and there was essentially a single synchronized global economic cycle. Of course, the Bretton Woods system that was at the heart of the 1960s world broke down in the early 1970s, with the result that the late 1970s, the 1980s and the early 1990s each witnessed quite disparate trends (and, as a result high levels of currency volatility). However, we would argue that the World started to move back towards a single global cycle by the end of the 1990s.

The Global Tech Bubble in the late 1990s, the Global Credit Boom that preceded the GFC in the mid-2000s, the GFC itself, and the relative uniformity of policy responses to the Financial Crisis, each had the effect of increasing the correlation between the cyclical positions of the World’s economies. Admittedly, the early- to mid-2010s witnessed some de-synchronization as China emerged and the Euro Crisis unfolded, but the weakness in world trade prices in 2015-16 and the a glut of dollar funding in 2017 increased the level of synchronization once again, most notably as growth in the US, EM and EZ revived in late 2017 on the back of a new – and as it transpired primarily dollar-funded - global credit boom. In fact, we would argue that the existence of a powerful dollar funded credit cycle between 2016 and 2019 placed the World firmly back on a 1960s’ style Dollar Standard.

Indeed, by late 2017, we would argue that the World had in effect moved once again back onto a Bretton Woods II type system – essentially a USD Standard in which many countries (including the PRC) had become heavily reliant on USD wholesale funding for their financial and quasi financial sectors. Hence, when US monetary conditions tightened in late 2018 (most likely by more than the Fed had intended), the World slowed soon thereafter. Of course, this year has witnessed an even greater synchronizing effect as the Covid-19 Crisis has hit, not least of all because there has been a near uniform policy response to the Crisis – led of course by the Fed.

In such a synchronized world, it is not at all surprising that USD liquidity trends have become “everything”, that correlations between asset markets have been high, and currency volatility has been low. We do wonder, however, whether 2021 will see a change in circumstances.

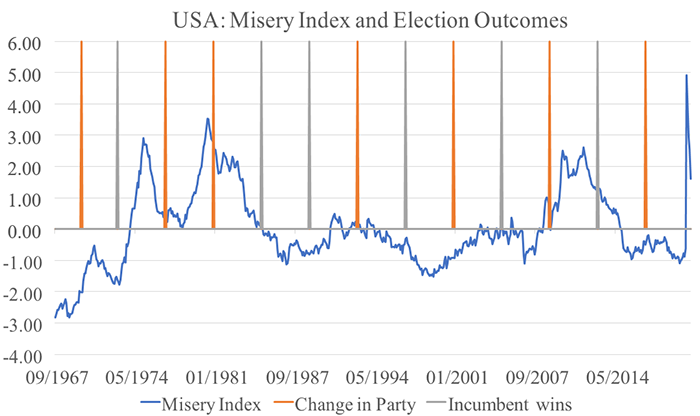

If there is any validity in our in-house ‘Misery Index’ predictor for the US Election, then we might assume that the Democratic Party will hold meaningful power next year and we can assume that there will be some form of fiscal package that is itself heavily monetized either by the Federal Reserve or (more likely) by the Treasury, via a running down in the Treasury’s own current substantial cash balances. These events will likely have the US liquidity and economic cycles ‘bottoming’ in March or April next year and the economy picking up thereafter. Alternatively, if President Trump is re-elected, then we might also expect some form of fiscal policy response in 2021H1 and most likely also a rapid run down in the Treasury’s cash balances – we suspect that the election result will likely shape the character of fiscal policy rather than its magnitude.

Crucially, we are also expecting that the focus of the US-Sino geopolitical friction next year will migrate from solely being in the physical trade arena (which attracts headlines but has had limited effects on quantities or prices) and move into the capital account, which we believe will represent a very serious increase in tension that will likely be much more disruptive to global systems.

Indeed, we believe that, almost regardless of the US election outcome, the US authorities will find a way – possibly with assistance from other countries – to introduce some form of de facto capital controls / quasi limit on China’s ability to raise dollars in the US financial markets. Steps have already been enacted to limit equity issuance by PRC entities but we expect that there will also be action taken to limit China’s access to dollars across the entire length of the yield curve.

Such an event would clearly be highly disadvantageous for the now dollar-funding-dependent PRC financial system, and we could easily see under such a scenario Beijing facing a significant deficit in its balance of payments that obliged it to either de-link and depreciate the RMB versus the dollar, or to introduce ‘hard budget constraints’ on its corporate sector (i.e. by slowing domestic credit growth) and to move to limit its expenditure on the Belt & Road Initiative.

The effects of a weaker Chinese economy and also the weaker BRI spending would of course reverberate around the global economy, and certainly adversely affect China’s obvious trading partners and those countries in Africa, Central Asia and the Pacific Region that have become dependent on what has amounted to soft funding from the BRI. As stresses emerged in these countries, policy responses would be required and, as different countries adopted differing regimes, the impact on their currencies would be varied but in general negative vis-à-vis the USD – unless a suitably outward looking US Administration felt able and willing to provide funding either directly or indirectly via the US financial markets to these countries (if only so that it could regain some of its previously lost soft economic power – the election result will matter here, we suspect). If Beijing were however to opt for a de-linking of the RMB from the USD, we would expect a weaker RMB and there to be a significant easing of domestic monetary policy within China.

Thereafter, an easier stance in China might well be supportive growth in the economy (and its trading partners) in the near term, but we would worry about the outlook for inflation in the PRC over the medium term – the loss of the country’s erstwhile monetary anchor (i.e. the dollar) and its already extreme level of excess money balances could easily result in a surge in inflation akin to that experienced by many other countries when the original Bretton Woods regime broke down in the 1970s. In this regard, we note Japan’s inflation experience in the early & mid 1970s – the rate of inflation in Japan moved from 4% in 1972 to 25% in 1974 as global monetary anarchy unfolded in the wake of the collapse on the Bretton Woods System. Given China’s ‘dominance’ within the global goods markets, we suspect that its inflation and currency strategies will ultimately determine global inflation trends.

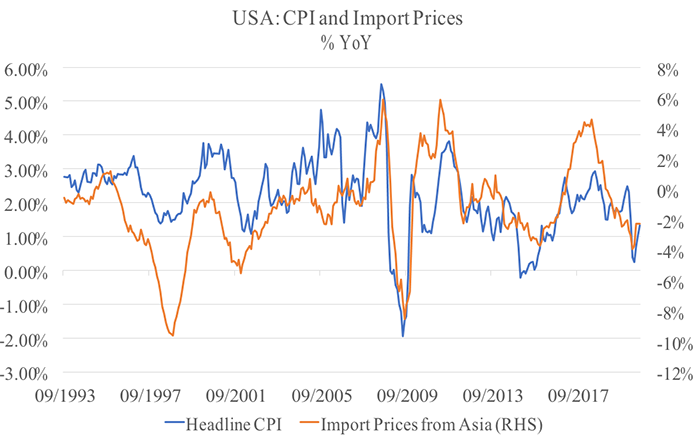

Many clients have recently asked us about the medium-term outlook for global inflation and we would suggest that much of the answer will lie with Beijing’s policy choices (as it often has since the early 2000s). We firmly believe that since 1992/3, most if not all inflation surprises in the USA have had their roots firmly in Asia and changes in the prices of the goods that the Region exports to Western consumers.

Elsewhere, Japan’s economy appears to be following its own relatively unique path. With the population both aging and shrinking, Japan’s private sector seems intent on producing ever larger financial surpluses, while the government seems loathed to incur large deficits. As a result, we can expect Japan’s current account surplus to remain large and although this will most likely be more-or-less offset by outflows of direct investment, the situation should lead to the Yen appreciating by default, unless of course the BoJ takes some form of extreme domestic monetary action – which now seems unlikely.

It is difficult to summarise the outlook for the Euro Zone, not least of all because countries’ own differences and problems are becoming ever more apparent in this time of stress. For the Euro itself, we believe that there are two dominant factors for investors to consider. Firstly, we note that for every EUR1 that the ECB creates through its asset purchases, the ECB’s balance sheet ultimately inflates by EUR2 because of the differing impacts that its asset purchases have on the balance of payments of the member states over the medium term, and hence on the size of the ECB’s TARGET2 ‘opaque credit system’.

For a number of reasons, heavy levels of bond buying by the central banks in the Periphery tend to produce very large balance of payments deficits in these countries that have in turn to be funded via these countries borrowing (seemingly infinitely) from the TARGET2 system (which is we have long believed essentially an ‘off-balance sheet credit system’ operated by the ECB). This is the situation that leads to the fact that for every EUR1 of assistance it provides governments, the ECB implicitly creates EUR2 of negatively yielding and therefore capital-sapping assets for the German, Dutch and Luxembourg banking systems.

This ‘doubling up’ effect will always be a source of friction and certainly a limiting factor on the ECB’s ability to act, unless the second factor that tends to influence the EUR comes into play. This second factor is the activities of the French banks, who from time to time borrow or repay large quantities of USD. When USD funding conditions are accommodative, France’s banks have shown themselves to be very willing (usually during the first two months of each quarter) to borrow vast quantities of USD in order to fund their activities both in Europe and around the World – an action that leads to both upward pressure on the EUR and to France becoming a creditor in TARGET2 – and thereby taking the ‘strain’ off Germany et al (which in turn gives the ECB more freedom to act). However, we have also observed that when USD conditions tighten – and particularly if this occurs towards the end of a quarter – then the French banks tend to borrow from within the EUR system to repay their USD debts, thereby placing downward pressure on the EUR but increasing the pressure on the TARGET2 system’s primary creditors and so limiting the ECB’s room for manoeuvre.

What this situation tells us is that, if USD funding conditions are relatively accommodative then the EUR will tend to appreciate, Europe’s internal frictions will tend to dissipate, and the budget deficits within the Periphery will be more easily financed. However, any tightening in US conditions through policy, regulatory environment or bank risk aversion tends to produce the opposite situation.

It therefore seems to us that Europe’s economic performance in aggregate next year will be determined by the product of China’s demand for imports, and the US’s monetary environment. If the EZ were to be one country, we suspect that it could have more leeway in determining its own path but, clearly, it is not in such a position. Therefore, we expect the EUR to move countercyclically with US monetary conditions.

Finally, and virus permitting, the UK and GBP may start the year relatively well on the back of a probable ‘BREXIT Deal’ but we suspect that this will be a short-lived respite; we can expect the nation’s Capital to remain vulnerable to the impact of ultra-low rates and Covid-19 on its all-important finance and hospitality sectors, thereby making it ever more imperative that the government takes action to stimulate the regional economies. Unfortunately, generating real change and real income growth in these regions will require long term structural micro economic reforms, none of which are even being considered at this time. Therefore, we can expect the government to fall back on a generalized monetary and fiscal stimulus that we suspect will result in the value of sterling being dependent on the level of value added and productivity in its less affluent regions. We expect an accommodative domestic stance and a weak currency will be the reality of Post BREXIT Britain.

Disclaimer:

Disclaimer: The information in this report has been taken from sources believed to be reliable but the author does not warrant its accuracy or completeness. Any opinions expressed herein reflect the author’s judgment at this date and are subject to change. This document is for private circulation and for general information only. It is not intended as an offer or solicitation with respect to the purchase or sale of any security or as personalised investment advice and is prepared without regard to individual financial circumstances and objectives of those who receive it. The author does not assume any liability for any loss which may result from the reliance by any person or persons upon any such information or opinions. These views are given without responsibility on the part of the author. This communication is being made and distributed in the United Kingdom and elsewhere only to persons having professional experience in matters relating to investments, being investment professionals within the meaning of Article 19(5) of the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000 (Financial Promotion) Order 2005. Any investment or investment activity to which this communication relates is available only to and will be engaged in only with such persons. Persons who receive this communication (other than investment professionals referred to above) should not rely upon or act upon this communication. No part of this report may be reproduced or circulated without the prior written permission of the issuing company.