Key Takeaways

- Renowned investor Warren Buffett has spotted the long-term attractiveness of Japanese companies and where Buffett leads, other investors tend to follow.

- Yet, there’s more to Japan’s renaissance than relatively inexpensive valuations. Companies have become more receptive to corporate reform and shareholder engagement; Japan’s services sector is benefitting from a resumption in tourism; and, in Japan, inflation is settling at supportive levels after years of deflation.

- These cultural and economic shifts suggest Japan’s recent soaring equity market won’t be a flash in the pan.

Japan has experienced quite a year so far. One of the highlights occurred in April, with a visit by Warren Buffett of Berkshire Hathaway. The timing of this visit, ahead of Japan’s full-year earnings season from April to May, proved quite symbolic. The “sage of Omaha” has a longstanding reputation for picking winners, and his visit really was a catalyst for Japanese equities to continue their march upwards. In July, both the TOPIX Index and the Nikkei 225 rose to their highest levels since 1990, and the positive momentum has continued since. Berkshire Hathaway subsequently increased its stakes in five major trading companies in Japan (Itochu, Marubeni, Mitsubishi Corp, Mitsui & Co and Sumitomo), cementing the world-renowned investor’s faith in Japanese businesses.

Global investors will have noted that Japanese stocks are benefiting from relatively cheap valuations, a long-awaited return of inflation and a weakening currency. But there are other, deep-rooted reasons behind the sustained progress made this year.

Japanese companies are becoming increasingly attractive to investors

One of the reasons why investors such as Buffett are increasingly excited about Japan is that recent changes to the way companies are run are already bearing fruit. Earlier this year, the Tokyo Stock Exchange (TSE) published new guidance for listed companies, urging them to come up with better financial strategies that focus on cost of capital and share prices. Effectively, the TSE asked companies trading with a price-to-book (P/B) ratio of below one to improve their financial practices to enhance shareholder value (a P/B ratio below one indicates investors have a less than positive view of the company’s future profitability).

Importantly, the ways in which companies can look to improve their P/B ratio—such as more investment in research and development (R&D), creating intellectual property and intangible assets, portfolio restructuring and investing in equipment and facilities for profitable projects – are all positives for investors. Another option for improving the ratio is to increase returns to shareholders, either by paying higher dividends or through share buybacks. Clearly in complying with the new guidance, Japanese companies are now moving in the right direction, all at the same time.

As an example, this year’s annual general meeting of a small cap machinery maker saw several shareholder-led resolutions aiming to bring the company “closer to its intrinsic value through friendly and constructive dialogue” successfully adopted, including one asking the company to significantly raise its dividends. This illustrates that the TSE’s reforms are supportive of shareholders, and shows that constructive dialogue can prove highly successful.

Post-COVID recovery bodes well for Japan’s tourism and services sector

Another welcome positive has been the consistent recovery of the services sector following COVID. The au Jibun Bank Japan Services purchasing managers' index (PMI) hit a record high of 55.9 in May, the ninth straight month where the services sector was well above the 50-mark signifying expansion. This impressive rate of growth dipped only marginally in August, down to a seasonally adjusted 54.3. And the services sector's strength can be attributed to the fact that in April, the Japanese government removed the last of its COVID-related restrictions, including cross-border measures. As a result, the recovery of Japan’s service sector is expected to continue as inbound tourism recovers.

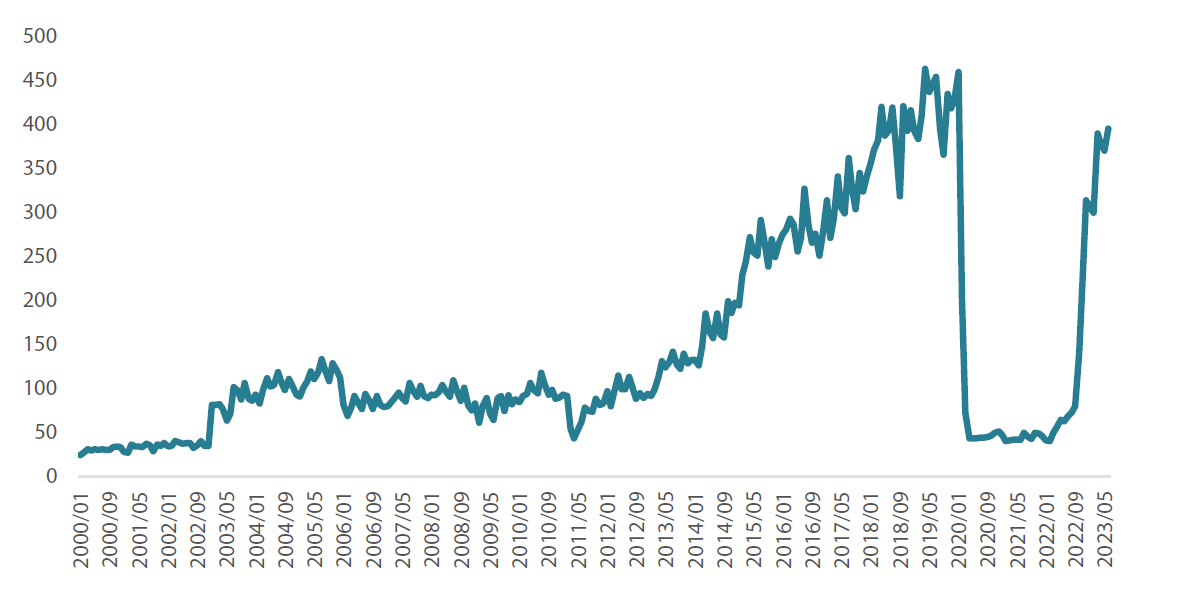

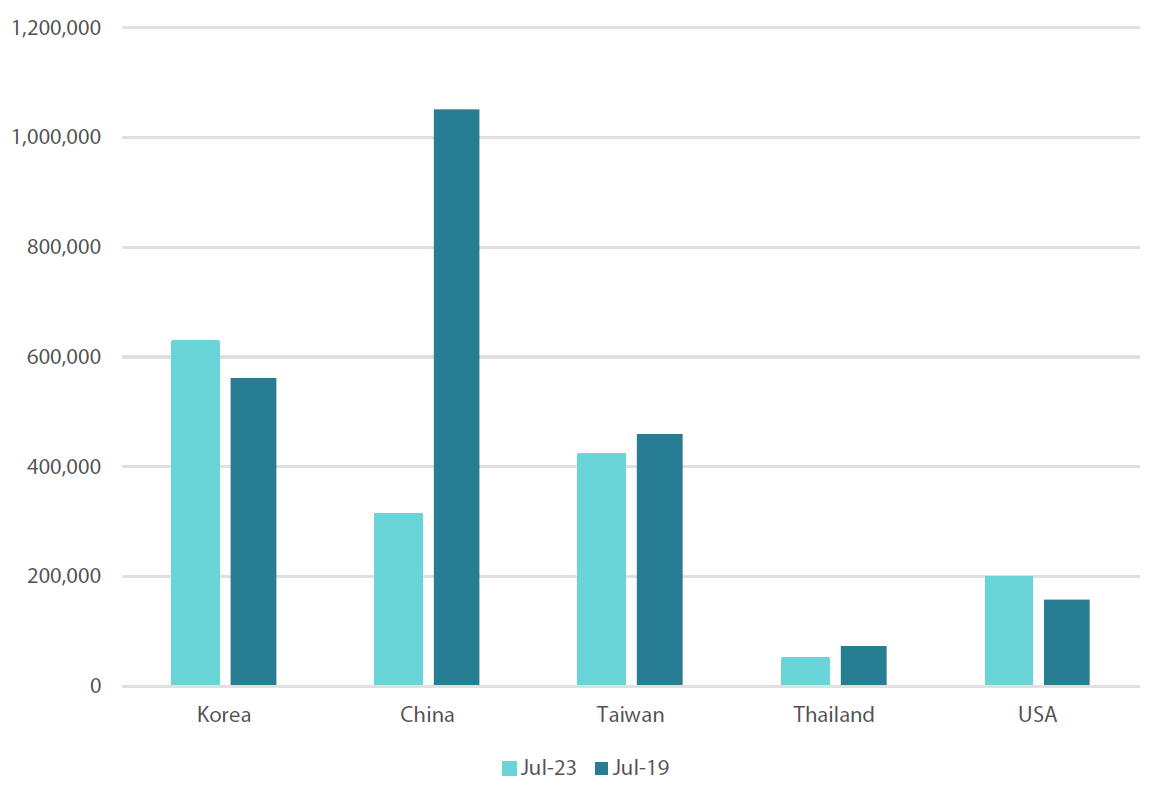

The return of Chinese tourists to Japan was the final restriction to be removed, and incoming tourism from the rest of the world has already returned to around 103.4% of pre-COVID levels, China’s tourism to Japan has understandably been slower to recover and is still down at around 30% of pre-COVID numbers. However, Chinese tourism looks likely to improve throughout the second half of the year. What’s interesting to note is that as a result of the Japanese yen weakness, tourism spending is outpacing tourist numbers, so even though tourist numbers haven’t yet reached their 2019 levels, aggregate spending is quickly heading toward prior levels. This means we can expect a much faster recovery path than we had expected just three to six months ago. We are no longer talking about a recovery in tourism, but a further growth in inbound tourism from here.

Chart 1: Monthly inbound tourism spending in Japan (JPY billions)

Source: Bank of Japan, June 2023

Chart 2: Monthly visitors to Japan

Source: Japan National Tourism Organization (JTNO), July 2023

Moderate inflation—not deflation—is the story of today’s Japan

Inflation in Japan has now been running above the Bank of Japan’s (BOJ) 2.0% target for 16 straight months. Celebrating inflation might sound incongruous, particularly given some Western economies are still finding it hard to combat rising prices, but deflation has historically been one of Japan’s biggest weaknesses, holding back investment and growth. However, with July’s core Consumer Price Index (CPI) inflation figure reaching 3.1% year-on-year, in line with forecasts, there are signs that cost-push inflation is beginning to peak in Japan, and inflation should slow in the second half of 2023. This should allow the BOJ to keep policy steady for the time being. With Japan’s long-term interest rate hovering around 0.6%, but with the US and Europe still tightening at much higher rates, the BOJ clearly has much more policy leeway than its global peers.

A combination of “fast” and “slow” investment

Foreign investors have also warmed to Japan this year, just as their view of China as the preferred investment destination for 2023 has cooled. Arguably the whole of Asia has benefitted from China’s disappointing economic performance this year, having failed to meet lofty expectations of an economic improvement after pandemic restrictions were removed towards the end of 2022.

As a result, global investors have been adding to their Japan allocation instead. This asset allocation switch has not just been restricted to so-called “fast money”. Increasingly, institutional investors are looking at the long-term investment case for Japan and seeing considerable value. Investors have also started to return to Japan for company visits, and in-person investor conferences in Tokyo that were mostly put on hold during the pandemic period. For investors looking to park their money longer term, investing in Japan is not just about the low-growth environment faced by Western markets. The corporate reforms now in place mean there is more long-term money being invested as well as shorter-term money. This brings us back to our earlier point about Japan’s much-improved corporate behaviour, and the reasons why this is expected to continue.

A cultural shift among corporates and investors is taking place

Japan’s push for corporate reforms, and the cultural imperative driving them, shouldn’t be underestimated. Companies are changing their behaviour and taking steps to anticipate and head off greater pressure from shareholders. The last thing Japanese companies want is to be named and shamed, so more companies are proactively making corporate improvements before their shareholders force them to.

Japan’s recent soaring success doesn’t look like a flash in the plan, as suggested by Japan’s long-term secular uptrend in corporate profits. Encouragingly, it is being sustained by the fact that Japanese companies are finally ready to engage with shareholders. And these days, institutional investors are finding themselves supportive of activist shareholder proposals where it makes sense to, as increasingly their interests are aligned on issues such as raising capital efficiency and improving boardroom diversity.

There is, of course, still some way to go. But the signs are encouraging. Corporate Japan is clearly no longer the “closed shop” it once was, and global investors are now starting to recognise the advantages that being open for business brings.

Any reference to a particular security is purely for illustrative purpose only and does not constitute a recommendation to buy, sell or hold any security. Nor should it be relied upon as financial advice in any way.