There is a growing view that the Pandemic, and the policy response to the Pandemic, have ended the period of Secular Stagnation within the Global Economy and potentially replaced it with “fiscally-led faster growth” and higher inflation. It is easy to see the logic behind this view; the author was an ardent inflationista only 18 months ago. The only flaw in the argument would appear to be the behaviour of the bond markets, which this year look superficially at least to have been embracing the concept of renewed economic stagnation.

As a starting point, we find it difficult to embrace the concept of faster trend growth within the global economy given the continued lack of productivity growth. Weak productivity growth and aging demographics in many of the world’s key economies make faster trend growth rates virtually a mathematical impossibility. The outlook for inflation is however harder to discern – will we see a dis-inflationary stagnation or simply stagflation? At present, the bond markets seem to be suggesting the former, although there must now be questions about just how much bond markets can tell us while they are in their current state.

It has long been our view that the authorities “broke” not only the bond markets, but also the long term savings industry, and parts of the banking system through their excessive use of Quantitative Easing since the GFC (and perhaps even before). The Pandemic-era QE was probably the final straw in a long running process that has left the debt markets unfit for purpose – particularly from the point of view of “real people”.

As a direct consequence, of this, we find that by 2021, the only people left “buying bonds” were those that had to because of regulatory constraints (including commercial banks); those that needed bonds for collateral; speculators running on a greater fool theory; and of course the omnipresent central banks. As the latter drove real yields down to absurd levels, “real world savers” understandably quit the markets in favour of equities, credit, crypto, property etc etc.

Indeed, we can easily argue that many of the people that can in fact sell bonds on a discretionary basis (i.e. in response to rising inflation) had already done so before the 2022 Inflation arrived. Instead, bonds were owned by entities requiring collateral (who ironically have to buy more bonds if bond prices fall), regulated entities, and banks - both central and commercial. We suspect that this factor limited by how much bond yields rose as inflation rates accelerated 18 months ago.

Unfortunately, the banks now have a particular problem with their bond portfolios. In many if not most cases, if they were to start to actively sell bonds on a discretionary basis (rather than simply letting them run off their balance sheets), the accounting conventions imply that they have to reclassify their entire portfolios as “items for sale” rather than investment securities and, as a consequence, they would have to mark their entire portfolios to their market value. For many commercial banks, the “hit” to their Tier One capital would be immense (i.e. a third or more!), and so they have developed a de facto bias to holding the instruments to maturity where they can.

For the central banks, the accounting conventions differ by country – the ECB has in theory to mark to market its giant portfolio if it begins selling proactively, but the Bank of Japan probably does not face such a potentially disastrous situation. The Federal Reserve and BoE have “fudges” available (the BoE can legally offset the assumed net present value of its future earnings from here to eternity against its losses, but we suspect that many politicos would see through such a sleight of hand). In New Zealand, the RBNZ can pass its losses onto the Crown via an Indemnity arrangement, but this is plainly not a costless exercise for the Crown.

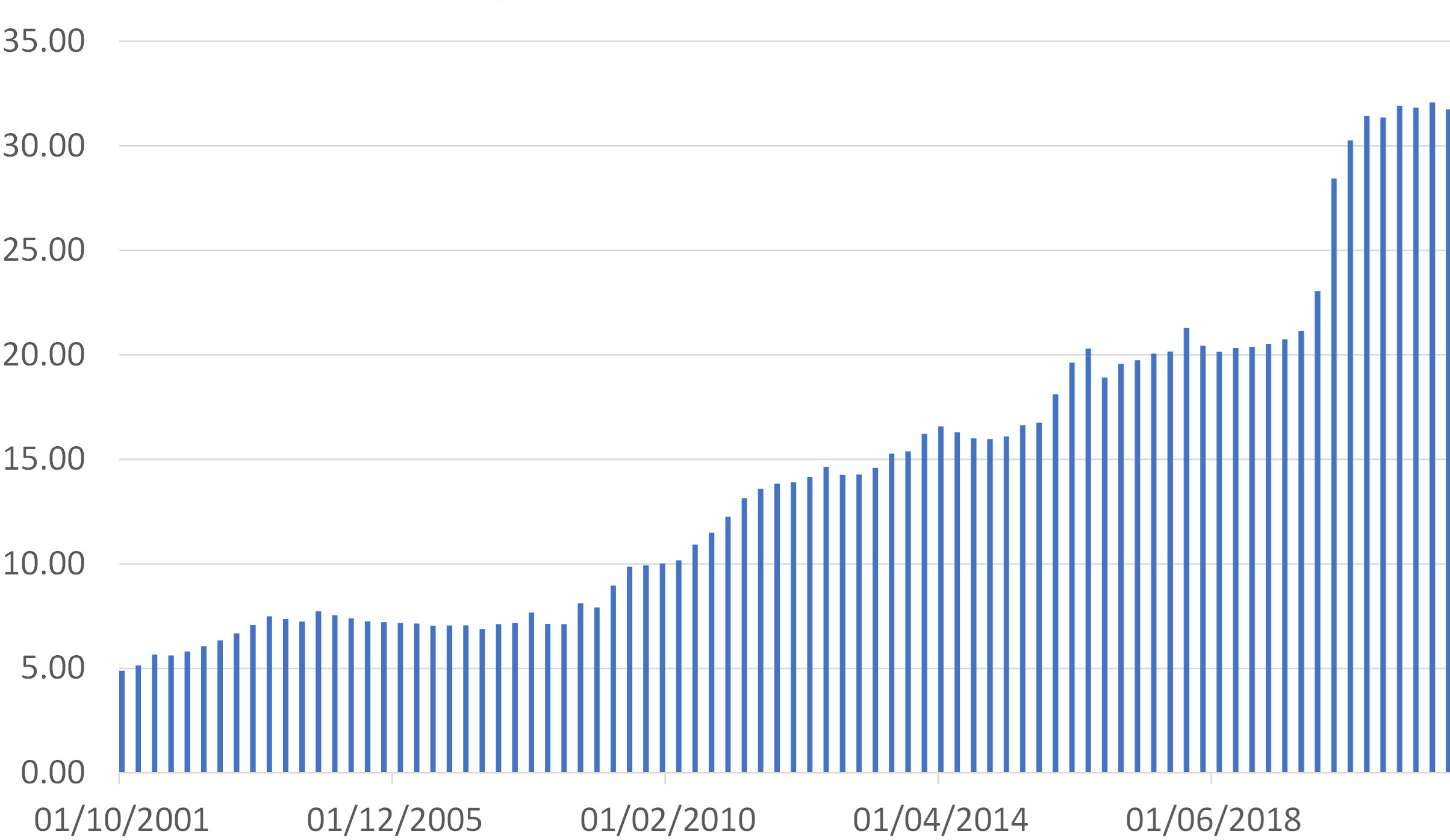

G7 Bank Holdings of Government Bonds

USD trillion, includes commercial & central banks

Clearly, the bottom line for much of the World’s banking system is that their bond holdings are now simply so large (i.e. the equivalent of 50% of Global GDP) and the potential losses so immense (and implicitly deflationary for their balance sheets) that their only viable strategy is to attempt to hold everything to maturity. This of course implies that a large chunk of their balance sheet will become immobile, with the result that if they face funding pressures (as some in the US are experiencing at present), they have to withdraw credit supply from the real economy. This, of course, is inherently deflationary for global growth even if the “lack of selling” by the banks results in lower yields than one might have expected.

Moreover, policymakers already revealed response to any downward pressure on bond prices has ranged from the mercurial in the case of the ECB (vis-à-vis its timing of QT and governments’ use of their cash balances) to the type of hair-shirt fiscal tightening that Messers Sunak & Hunt seem to favour in the UK. The latter is of course also explicitly deflationary at a time during which another important headwind to global growth is emerging.

China’s domestic economy has of course provided a significant (probably the most significant) source of Global Growth since the GFC. However, China’s middle classes are today facing what amounts to an unfolding balance sheet recession dynamic that will leave the country dependent on its current account surplus for what growth it can muster over the medium term, then China’s relative stagnation will add to a global stagnation theme that at times will likely be deflationary.

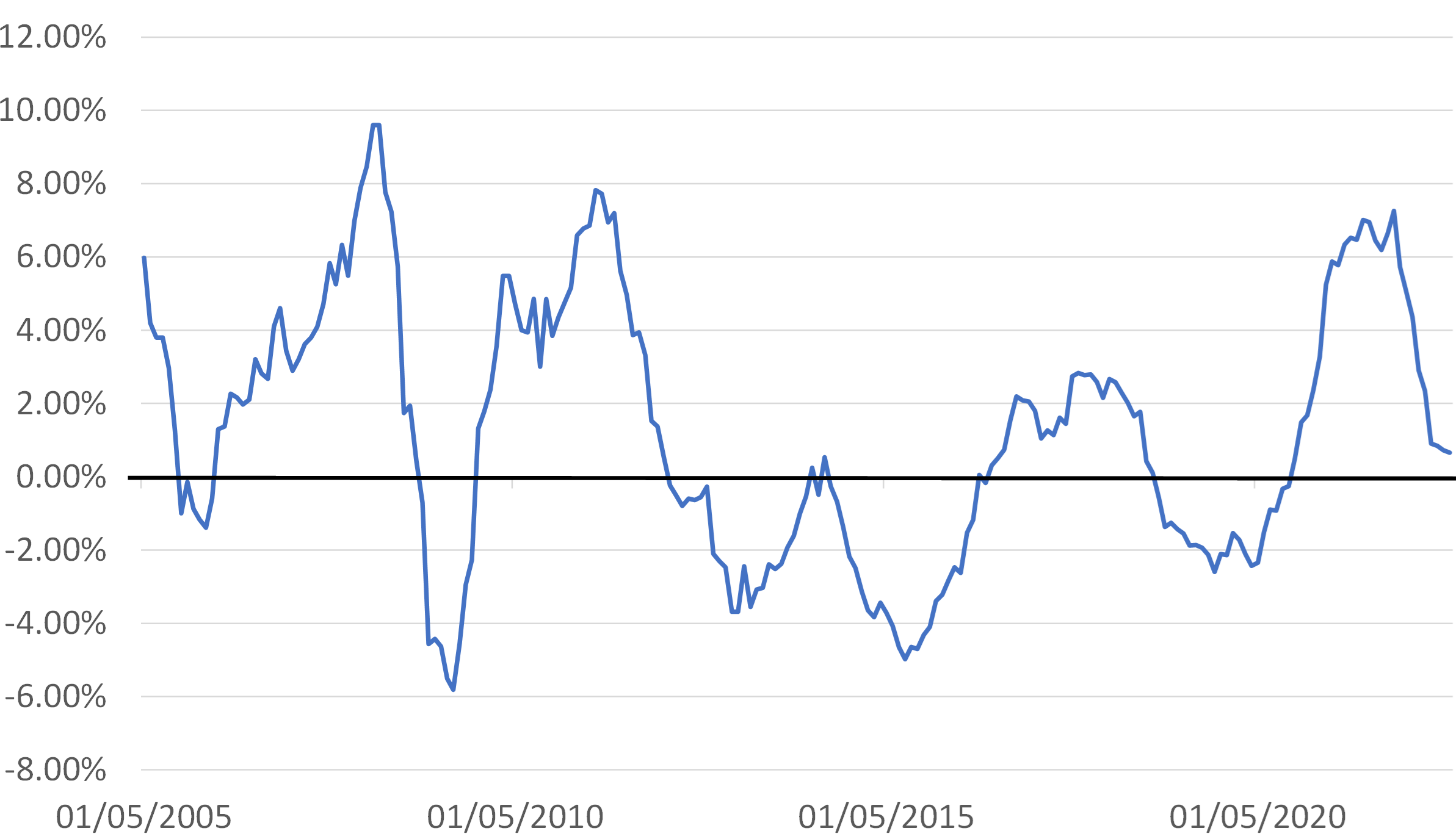

In fact, it is our working hypothesis that, when global growth is weak, the PRC will attempt to reduce its export prices via both a softer RMB bias and actual price cuts in an effort to protect its current account surpluses. However, whenever global growth revives, we would expect the PRC’s cash-strapped companies to chance raising their export prices and the PRC may even favour a stronger RMB (to ease the FX debt burden) during such periods.

As a consequence, we expect China to be a profoundly deflationary influence during periods of global weakness but an inflationary one during recovery phases, when they occur. This has been a feature of the Asian Export Price cycle for some time, but we expect it to become even more obvious over the coming years; we look set to witness periods of Goldilocks, deflation and inflation across the duration of the Asian / World Trade Cycle.

Asia: Export Prices in USD

% Yoy, export weighted

Faced with obvious governmental funding issues that we have described in previous reports, and the potential for sustained subdued growth, there will of course be a temptation amongst policymakers to revert to QE – perhaps as soon as the latter part of this year.

However, as 2021 revealed, holding yields down and adding liquidity artificially will tend to be inflationary, particularly if the China Cycle dynamic that we describe above unfolds. Under such a model, the current global dis-inflation would turn quickly back to inflation in 2024 if Quantitative Tightening were to be abandoned in favour of QE again.

Conspiracy theorists will of course see this as an opportunity for governments to reduce the real value of their debt by inflating away its value away but we wonder whether years of minimal real income growth for median households around the world will really allow this to happen – as we witnessed in 2022 the political backlash against inflation can be severe; endless QE may therefore not be sustainable either.

All of this suggests to us that we may be entering a period of perpetually sluggish trend growth – with rapid short term mini-booms and busts over the next few years (very Japan like) but a pronounced inflation / dis-inflation cycles (more like the 1970s). In short, we can expect to experience a lot of economic noise around a continued secular stagnation in growth but inherent price and inflation instability. It seems that we may therefore not be about to free ourselves of the tyranny of trading QE & QT in markets. With this in mind, we would position for QT in Q2 (higher yields & weaker growth) but by Q4 we may be looking to QE and lower yields & economic stimulus.

Disclaimer: The information in this report has been taken from sources believed to be reliable but the author does not warrant its accuracy or completeness. Any opinions expressed herein reflect the author’s judgment at this date and are subject to change. This document is for private circulation and for general information only. It is not intended as an offer or solicitation with respect to the purchase or sale of any security or as personalised investment advice and is prepared without regard to individual financial circumstances and objectives of those who receive it. The author does not assume any liability for any loss which may result from the reliance by any person or persons upon any such information or opinions. These views are given without responsibility on the part of the author. This communication is being made and distributed in the United Kingdom and elsewhere only to persons having professional experience in matters relating to investments, being investment professionals within the meaning of Article 19(5) of the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000 (Financial Promotion) Order 2005. Any investment or investment activity to which this communication relates is available only to and will be engaged in only with such persons. Persons who receive this communication (other than investment professionals referred to above) should not rely upon or act upon this communication. No part of this report may be reproduced or circulated without the prior written permission of the issuing company.