Currently, the US economy is stuttering. Headline growth during the latter half of 2023 was extremely rapid – GDP growth averaged more than twice the economy’s 20-year average - but this strong activity was led by the public sector, either directly through government investment or indirectly via the authorities’ support for household incomes. Moreover, the resulting budget deficit was (in effect) almost fully monetized, albeit via a relatively convoluted process involving extreme levels of Treasury bill issuance that was primarily sold to the Money Market Funds, specifically so that the latter were able to rundown their “sterile” deposits at the Federal Reserve.

Quite simply, the fiscal stimulus in 2023 was huge and more akin to a wartime situation or crisis period than “level flight” in the economy. Crucially, we find that the government’s heavy dissaving did not boost economy-wide profits by as much as one might have expected, a symptom we believe of the lingering malaise in the private sector that has resulted from the ongoing weak productivity trends and the heavily distorted pricing of property versus goods prices and wages. Away from the hyperbole over AI themes, realized productivity growth has been weak for a decade and this has depressed real income trends at a fundamental level.

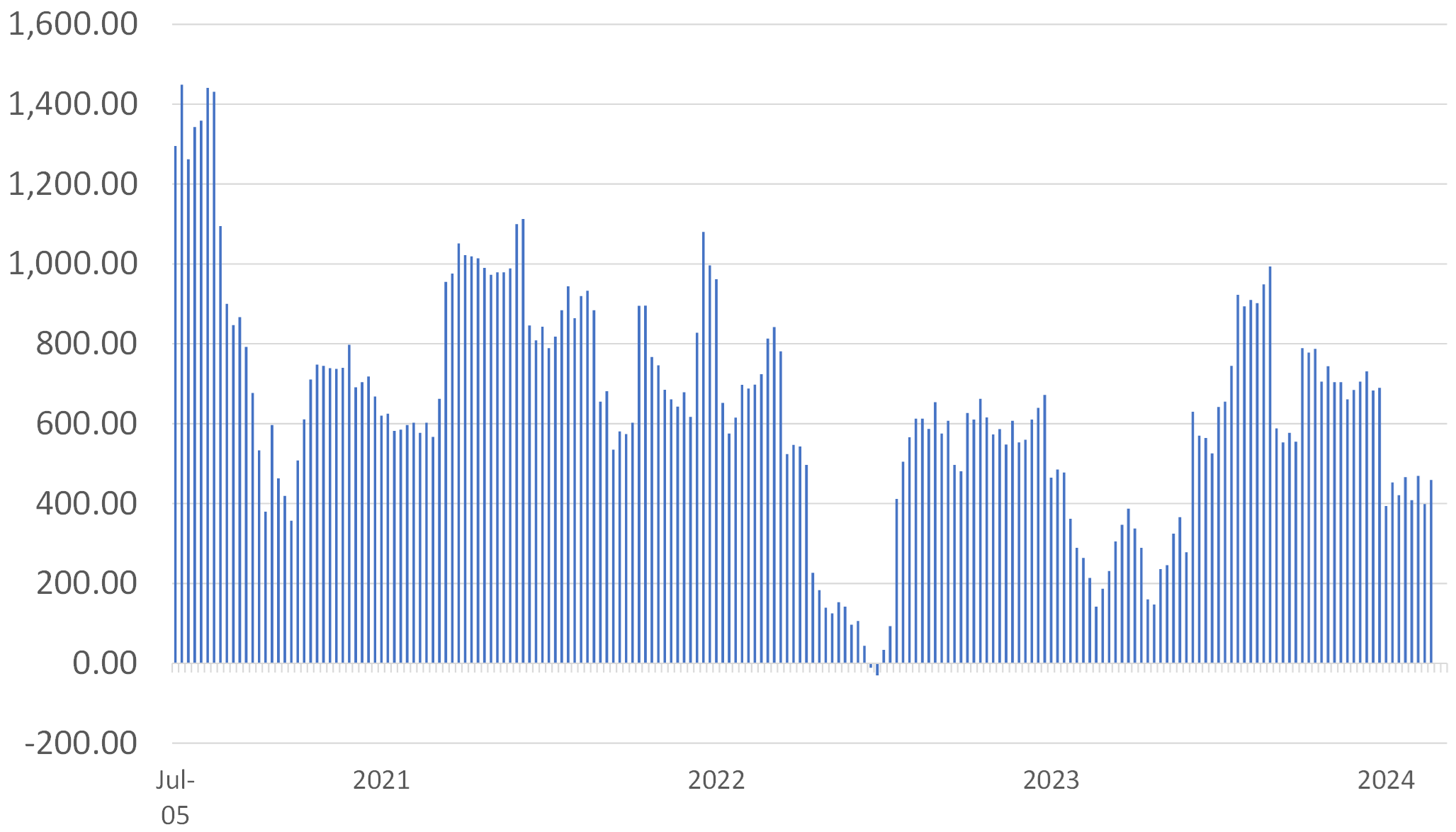

Perhaps a little surprisingly, much of the fiscal support for the economy has been withdrawn over the last two months. The budget deficit has contracted significantly and there has been rather less implied monetization of the remaining deficit. Robbed of this support, economic growth in the private sector economy has predictably become erratic and patchy. It also seems to have become confined to the wealthier parts of society; we are told that spending patterns amongst those that earn less than $50k per annum are now quite depressed. Since the turn of the year, there have been good weeks and bad weeks, that have served to provide an at times confusing signal, but in general the economy seems sluggish now that the fiscal life support has been turned down.

USA: Budget Deficit

USD billion over rolling 13 weeks

There is no definitive answer as to why fiscal policy has tightened so aggressively over recent weeks but the general assumption – with which we would concur – is that the authorities are merely husbanding their spending ammunition for later in the Election Race. Several senior Democrats have talked of this election representing a “fight for democracy”, and certainly the impression that we gained while in the country a few weeks ago was that “the end justifies whatever means are required”.

Consequently, we expect the pace of fiscal spending to revive next quarter and the Treasury can also be expected to seek to monetize the resulting deficit by tapping both the remainder of the Money Market Fund / Reverse Repo liquidity reservoir that we referred to earlier, and also drawing on the government’s own now very large accumulated cash reserves. By utilizing their existing cash reserves, the Tresury can avoid issuing bonds (issuing longer term debt tends to draw liquidity out of the system) and instead inject their own cash back into the system via their spending programmes.

This may seem like an attempt at blatant electioneering but in reality it is no more than the Nixon/Ford Administration orchestrated, with the active if not entirely willing help of the Arthur Burns-era Federal Reserve during the early and mid-1970s. The end is likely seen as justifying the means and the result will likely be a stronger economy around midyear. Unfortunately, we expect this to prove inflationary.

Our work suggests that the US economy still possesses a modest positive output gap. Certainly, our in-house capacity utilization indictors continue to look elevated. This situation has resulted in the sticky – and in places still accelerating - inflation in parts of the domestic service sectors. Of course, if economic growth re-accelerates to a likely above trend rate over the middle part of the year on the back of a new fiscal stimulus, then we can assume that the output gap will widen further and the economy will find itself facing yet another inflationary episode at the turn of the year. The risk to this forecast is of course that the authorities do not ease fiscal policy again, but this seems an unlikely scenario.

In addition, the Federal Reserve may reduce short term interest rates during the second quarter, as the current soft growth and potentially some good inflation news from falling import prices provide the necessary cover for such a move. However, we suspect that by the end of the year the central bank will be thinking about raising rates once again. The Presidential Election will delay the timing of any hikes, but we fully expect the by-then-strong US economy to find itself facing a new fiscal & monetary policy tightening cycle in 2025. This could prove to be problematic for the rest of the world.

China’s economy has stalled and looks to be succumbing to an unfortunate combination of a balance sheet recession within the household sector amd a politically-motivated fiscal tightening. China’s economy looks to have entered a significant and protracted slump, the consequences of which will continue to undermine local equity prices and the currency, while also reverberating around its trading partners both in the Asia Pacific Region and further afield.

Europe’s economy is ill-placed to weather the storm. Over-regulation, deteriorating credit availability, flawed energy and industrial policies, and the overtly politicised nature of policymaking over recent years have left the Region inherently sclerotic and as a consequence reliant on either fiscal stimuli or external drivers for its growth. This year, we suspect that fiscal policy will remain relatively accommodative but that its marginal effect will wane, while China’s continued weakness will constrain any external sources of growth. The European Central Bank may have quietly switched back to a Quantitative Easing policy since the selloff in bonds markets last October, but they seem to be gaining little traction at this point outside of knee-jerk rection in equities. With Europe’s once positive output gap turning negative, the ECB will soon need to lower rates explicitly, something that will likely widen the gap between USD and EUR rates over the next 18 months, with adverse implications for the currency.

It may seem strange that Japan’s economy is shrinking but at the same time it is also apparent that inflationary pressures are rising. This unusual state of affairs has arisen because Japan’s weak productivity and shrinking labour force is causing the economy’s ability to supply goods and services to decline at an even faster pace than Demand is falling. In theory, the Bank of Japan needs to raise interest rates despite the ongoing technical recession, and we suspect that they will raise rates by a token amount over the coming months, but in reality we do not expect Japanese yields – at any point on the curve – to rise by more than 25b.p. this year. Indeed, low rates and strong liquidity should keep the Japanese equity theme “alive” even as the JPY continues to depreciate over time.

In summary, if the US conducts an inflationary fiscal stimulus over the next few months, as we believe that it will, then the US will end 2024 facing the prospect of materially higher inflation, higher yields and most likely a monetary tightening as well. This will likely set the US on a very different course to the other major economies, something that should buoy the dollar but also signal the end of the de facto US Dollar standard that the global economy has been operating on over recent decades. The latter part of the 2020s should therefore see higher degrees of currency volatility than we have become accustomed to over recent years.

With regard to the equity markets, we suspect that the authorities’ likely gung-ho approach to policymaking will continue to provide support to the indices, although in reality we suspect that it will only be a handful of theme & liquidity driven stocks that make most of the running. As we have written before, one of the most powerful scenarios for equity prices is a liquidity-driven rally that is centred around an unquantifiable theme. We suggest unquantifiable here simply because in our experience the rationale for the rally becomes a question of faith and belief rather than hard facts, something that tends to both encourage speculation and make life harder for would-be Cassandras. If there is nothing concrete to analyse, it is difficult to argue against the theme as the late 1990s and even last year proved.

Disclaimer: These views are given without responsibility on the part of the author. This communication is being made and distributed by Nikko Asset Management New Zealand Limited (Company No. 606057, FSP No. FSP22562), the investment manager of the Nikko AM NZ Investment Scheme, the Nikko AM NZ Wholesale Investment Scheme and the Nikko AM KiwiSaver Scheme. This material has been prepared without taking into account a potential investor’s objectives, financial situation or needs and is not intended to constitute financial advice and must not be relied on as such. Past performance is not a guarantee of future performance. While we believe the information contained in this presentation is correct at the date of presentation, no warranty of accuracy or reliability is given, and no responsibility is accepted for errors or omissions including where provided by a third party. This is not intended to be an offer for full details on the fund, please refer to our Product Disclosure Statement on nikkoam.co.nz.