We have little (in fact, virtually no) doubt that the opening salvos of the monetary response to the Pandemic were driven by a sense of panic rather than by calculated analysis. The Federal Reserve appeared to be downplaying internally as well as externally the impact of the Pandemic as late as on the 11th March 2020, but by lunch time on the 12th March it was in full crisis mode. As to whether the sudden shift in stance was driven by fears for the real economy, or the news that some large leveraged funds had been caught disastrously the wrong side of heavy Treasury bond selling by Emerging Market central banks may be forever unknown….

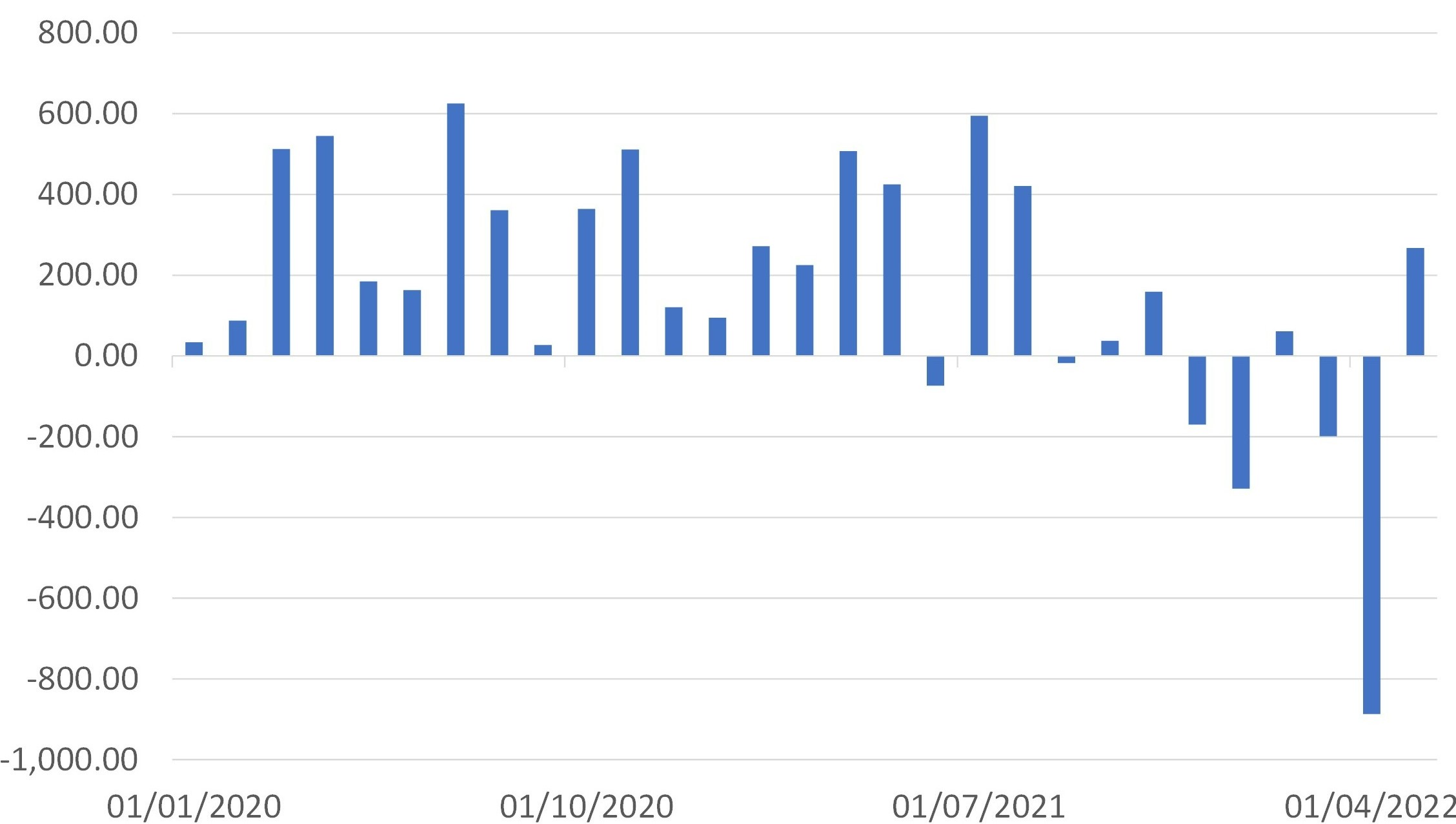

Once the initial crisis phase had passed, however, the Federal Reserve and other central banks moved towards a sustained period of asset purchases that was primarily designed to control bond yields / support bond prices, even as governments ramped up their deficits and hence funding requirements. Although the government bond purchase programmes were not in fact a deliberate Quantity measure, but they were, quite simply, immense and they gave rise to a virtually unprecedented inflation of the money supply. Somewhat surprisingly, and certainly inappropriately, the stimulus continued well into 2021 even as the vaccination programmes led to a gradual re-opening of the global economy.

G20 Central Bank Net Purchase of Govt Debt

USD billion monthly, prevailing FOREX rates

The essence of the policy response in 2020 - 21 was to support financial wealth and hence demand within the private sector, while facilitating the funding of the large fiscal stimuli. For those in the real world, the thought of adding 10 – 20% more money to economies that could produce less (because of the lasting impact of the lockdowns and ongoing supply constraints) could only ever have been expected to be inflationary – first financial asset prices, then land prices, and finally the general price level all inflated. There was, quite simply, now more money now chasing the same number of equities & houses, and fewer things in the real economy.

In their complex maths-heavy / group think world, policymakers seem however to have eschewed common sense and assumed that the “supply curve” was somehow elastic and that the only constraint on output & real consumption was the level of demand. We are not sure why this assumption was made – we can only assume that it is the result of the way that economics is taught at those relative few academic institutions that today supply policymakers.

Of course, this is not the first time that seeming nonsensical assumptions (from the point of view of “real people”) have been made by policymakers & markets – at the heart of the GFC / Mortgage Crisis in 2008 was the rather counter-intuitive assumption that the behaviour of the various regional property markets of the US were not somehow corelated with each other. The man-in-the-street would of course have expected all the major markets to weaken when borrowing costs rose, but the mathematicians in the banks, rating agencies and regulators somehow decided that this would not be the case, and it was this unexpected correlation that caused the mortgage derivative markets to collapse. Keynes once remarked that practical men are unwittingly hostage to the long-forgotten writings of some redundant economist, but the truth seems to be that the mathematicians have taken over….

Last year of course delivered two fundamental lessons. Firstly, supply curves are not in fact horizontal (what economists call price elastic) and that when you raise demand relative to supply, inflation occurs. The second lesson was that bond markets will not necessarily “bark” when inflation rises if their own internal supply and demand positions are being distorted – or even controlled – by the authorities. We note that all of the angst over the recent sharp sell-off in UK Gilts, and the consequent demand for economic austerity by this week’s British government, rather neatly sidesteps the fact that UK bond yields never should have been as low as they were (given inflation and the deficit) and were only that low because the Bank of England had bought so many of them….. Markets often seem to lose perspective at times such as these.

UK: 10 Year Bond Yield Adjusted for Inflation % pa

Returning to the issue of supply curves, we are beginning to think that not only are they not horizontal (elastic), they may be becoming close to being vertical (inelastic). In Europe’s energy constrained economies, this is of course any easy proposition. In the UK, a lack of labour and transport bottlenecks also hint at supply inelasticities. In the USA, the goods markets are becoming more elastic as Asia looks to dispose of its rising inventories, but there are clearly still binding bottlenecks in the service sectors.

However, these are not the only factors causing supply inelasticity. We recently attended the annual dinner of a business forum and in an hour and a half of speeches, we heard about climate change, wider stakeholders in business and a need to consider the wider “externalities” of doing business. These are all very worthy causes and, as a regular business traveller the author has had a front row seat on the changes in the planet’s appearance over the last 30 years. A little ironically, I certainly think much more about my carbon footprint after flying over familiar glaciers and Central Asia for so many years.

The Western economic model has relied on profit maximization and unfortunately if generally failed to fully account for all of its costs (i.e. the costs to others of its operation. The concept was not at fault, merely the accounting…). The North Asian Development Model focussed almost solely on output and employment maximization, largely for political reasons. It is only right that both these models should now be modified and, until technology comes up with a solution to the externalities problems (which one day we assume that it will), this implies that we will be able to produce less / grow less.

Unfortunately, most governments - of whatever hue - have not yet told their populations this inconvenient truth, and if our recent business dinner is anything to go by, neither have companies. Leaders still seem to be promising that we are in a world of elastic supply curves, despite their recent experiences.

We could therefore be moving to a period of endemic excess demand (although probably not in 2023, when we do expect quite a deep demand recession, but certainly over the longer term). This, of course, then raises the question as to how are we going to allocate the increasingly finite level of supply to those that would consume it, both at a micro and macro level?

Planned economies may seek to use rationing and direct resource allocation, while others may fall back on the old Soviet method of using queues until the item in question simply runs out. More capitalist-leaning systems will of course use the price mechanism, although as we have seen this can quickly become a “cost of living crisis” as some people are priced out of buying the things that they want. The price mechanism tends not to be very compassionate, and it will only allocate resources to whomever will and can pay.

This competition for supply will also extend to competition between countries for resources. Such a world will favour those with either their own supply of resources (the USA does well here), or a strong enough terms of trade to allow them to buy the things from abroad that they want at a price that they can afford.

Resource poor economies with weak export price trends will likely be highly disadvantaged. In times of inflation and competition for supply, one should favour companies that can control their costs and the same is true for countries – high export prices and / or a limited demand for imports will be the countries to look for in such a world. During the late 1970s, resource-poor Japan performed well thanks to its strong terms of trade and its experience tells us much about which countries may perform relatively well over the medium term.

Of course, less scrupulous regimes may try to use force to gain control of what they need Ukraine is of course resource rich and the “Great Game” is once again being played in Asia, Africa and LATAM. Governments may be tacking back to austerity but the need for higher defence spending will likely remain ever-present.

What does all of this mean for investors? In a world of competition for supply, inflation will likely become endemic over the medium term (unless policymakers actually decide to “fess up” to the new supply constrained world) and this should one day become toxic for the fixed income markets, and for the credit markets in general (zombie companies may finally be wiped out by rising costs).

In the near term, we fear that a supply glut will push UST prices lower (a flash crash in bonds is possible over the next few weeks?) but, as this year draws to a close, we expect the by then rapidly approaching demand recession to allow the T10 year to move back to below 3.5% yields as dis-inflation occurs. However, as soon as policymakers react to the economic weakness and start to allow demand to recover, we expect competition for resources to increase and inflation rates to leap once again, raising the prospect of an annus horribilis for bond markets in 2024 (the exact timing will depend on whether western governments stray into Yield Curve Control policies in the interim, a not impossible scenario judging by the Japanese and UK central banks’ recent activities).

Equity markets, facing weakening earnings trends will become dependent on valuation trends and this will likely be determined by the course of bond yields. There will however be individual companies that prosper (productivity enhancers, tech users or developers?).

In the World that will likely emerge after next year’s recession, investors should probably look to focus on countries with strong terms of trade, consistent anti-inflation macro policies and hard currencies. Certainly, we expect more currency volatility over the medium term than we have become used to since the mid-1980s, something that could add to the ECB’s list of problems. Countries with weak terms of trade and short-term populist regimes should be underweighted.

The new world order will likely see more rather than less trade friction & more onshoring by those that can afford to do so. Unfortunately, the prospect of more regional conflagrations is also rising, and we can assume that rising inflation-induced-poverty will oblige more people to look to become economic migrants, not only between countries but even between regions. The exodus from Southern Italy to Milan, for example, may accelerate along with from poorer countries in general.

In short, we believe that the world of Cooperation and Globalization that set the tone for financial markets between 1985 and 2020 is rapidly fading – although it may return briefly for a final encore early next year as China’s recession allows world trade prices to deflate. The World that will replace this model will be one in which there is at times intense competition for supply and a greater distribution of outcomes between competing countries.

Disclaimer: The information in this report has been taken from sources believed to be reliable but the author does not warrant its accuracy or completeness. Any opinions expressed herein reflect the author’s judgment at this date and are subject to change. This document is for private circulation and for general information only. It is not intended as an offer or solicitation with respect to the purchase or sale of any security or as personalised investment advice and is prepared without regard to individual financial circumstances and objectives of those who receive it. The author does not assume any liability for any loss which may result from the reliance by any person or persons upon any such information or opinions. These views are given without responsibility on the part of the author. This communication is being made and distributed in the United Kingdom and elsewhere only to persons having professional experience in matters relating to investments, being investment professionals within the meaning of Article 19(5) of the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000 (Financial Promotion) Order 2005. Any investment or investment activity to which this communication relates is available only to and will be engaged in only with such persons. Persons who receive this communication (other than investment professionals referred to above) should not rely upon or act upon this communication. No part of this report may be reproduced or circulated without the prior written permission of the issuing company.